Joseph Lister and the Antiseptic Revolution

Discover how Joseph Lister transformed medicine with his antiseptic practices, paving the way for safer surgeries and infection control.

In the mid-1800s, hospitals saw nearly half of surgery patients die from infection. This was not from the surgery itself, but from infections that came later. Today, we can leave the clinic with a bandage and a plan, thanks to this change.

You might have benefited from Joseph Lister without even knowing his name. Before his work, surgery was a gamble. One cut could save you, while another could lead to a deadly infection.

The antiseptic revolution changed everything. Lister, a medical pioneer, believed in Louis Pasteur’s germ theory. He wondered if tiny organisms caused wound infections.

He tested carbolic acid on wounds and saw infection rates fall. His 1867 Lancet articles shared his findings. Slowly, operating rooms became cleaner and safer, thanks to Lister.

Key Takeaways

-

Joseph Lister made surgery safer by fighting infection early on.

-

The antiseptic revolution linked germ theory to wound infections.

-

Carbolic acid was Lister’s first tool to kill germs in surgery.

-

His 1867 Lancet articles spread antiseptic surgery far and wide.

-

Lister’s ideas shaped modern infection control and surgical hygiene.

-

As a medical pioneer, Lister changed what patients could expect after surgery.

Introduction to Joseph Lister’s Contributions

Ever wondered why surgery isn’t a gamble anymore? Meet Joseph Lister, the game-changer. He didn’t just tweak a few things in the OR. He changed what people thought was possible. That’s why he’s called the Father of modern surgery.

His approach was simple yet groundbreaking. He believed in measuring results and facing the ugly truth (like infections). This careful, curious mindset made him a lasting figure in medicine.

Who Was Joseph Lister?

Joseph Lister was born in 1827 in West Ham, England. His family, Quakers, valued hard work and facts. His dad, Joseph Jackson Lister, improved microscope lenses, encouraging his son’s interest in science.

At University College London, Lister learned by doing. He started as a dresser and later became a house surgeon. In Edinburgh, he worked under James Syme, where skill was tested, not just talked about. Lister became known for his practical approach and constant questioning.

| Snapshot | What It Shows About Joseph Lister | Why It Matters in Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Quaker upbringing in West Ham | Focus on discipline, observation, and doing the work | Helps explain his no-nonsense approach to reducing infection |

| Microscope influence from Joseph Jackson Lister | Comfort with close inspection and evidence | Supports the careful study that feeds Listerism |

| Training at University College London | Early responsibility in real hospital settings | Builds practical skill and a habit of tracking outcomes |

| Edinburgh experience with James Syme | High standards and constant exposure to surgical risk | Sets the stage for pushing antiseptic routines into daily practice |

The Importance of His Work

Before Lister, infections after surgery were common. He linked infections to germs, building on Louis Pasteur’s work. His goal was to keep germs out or kill them before they spread.

This shift changed how wounds were treated and tools were handled. Listerism became a mindset about safety and prevention. It’s why Lister remains a key figure in surgery’s history.

The State of Medicine Before Lister

Walking into a mid-1800s hospital was tense. Surgery was fast, but keeping things clean wasn’t a big deal yet. Doctors didn’t link tiny living things to infections, so they just tried to keep things smelling okay.

This lack of understanding changed everything in the operating room. It made antiseptic surgery seem shocking but also very needed.

Common Surgical Practices

Doctors wore heavy coats that might be stiff with dried blood. They used the same instruments without much cleaning. Bedding and dressings weren’t washed well, making hospitals dangerous places to get better.

Wounds looked bad, but doctors thought pus was normal. This made them not focus on keeping things clean. Today, we know how important it is to keep things clean in surgery.

Some doctors believed in miasma theories. They thought bad air caused sickness, including in wounds. So, they didn’t think about using antiseptics because they didn’t see the problem in the tools or dressings.

| What surgeons noticed | Common belief at the time | What it meant for daily care |

|---|---|---|

| Wounds often produced pus | Suppuration could be part of “healthy” healing | Less urgency around surgical hygiene and clean dressings |

| Hospitals had strong smells | Bad air (miasma) spread infection | Ventilation mattered more than infection control at the bedside |

| Outbreaks spread through wards | Blame fell on air, weather, or “ward conditions” | Tools, coats, and hands weren’t treated as key risks |

High Mortality Rates in Surgery

Post-op infections were common and expected. Erysipelas, pyaemia, and gangrene spread fast. At University College Hospital, Joseph Lister saw an outbreak in a male ward. It started with 12 cases and 4 deaths.

Treatments were harsh. Patients might be chloroformed, have dead tissue scraped off, and be treated with mercury pernitrate. Sometimes it helped, but often it didn’t. In those days, fighting infection was a tough battle. It was about stopping amputation or worse before antiseptic surgery became common.

The Birth of Antiseptic Techniques

Imagine a hospital in the 1860s. It was full of blood, bare hands, and guesses about infections. Then, new ideas came. Microbes were discovered, changing how we fight infections.

This change didn’t stay in labs. It moved to operating rooms. There, it started a new way of keeping surgeries safe.

Key Discoveries in Microbiology

Joseph Lister was inspired by Louis Pasteur’s work. Pasteur showed that air could spoil liquids. This led to understanding tiny living things in the air.

When air meets an open wound, bad things can happen. Lister thought a barrier was needed to protect wounds.

At first, it was hard to tell good microbes from bad. So, Lister focused on keeping everything clean. This was the start of infection control.

The Role of Carbolic Acid

Carbolic acid, or phenol, was known for killing germs. Lister used it to clean wounds in 1865.

He tested it on a boy with a broken bone. The wound healed without infection. This was a big success.

From 1865 to 1867, Lister treated 11 patients. Nine didn’t get infections. His work was published in The Lancet, showing the power of carbolic acid.

| What Lister leaned on | What you’d notice in practice | Why it mattered for infection control |

|---|---|---|

| Pasteur’s findings on airborne microbes | Less spoilage when milk and juice were protected from air | Made wound infection look like a preventable chain of events |

| Antiseptic “shield” thinking in early Listerism | Attention shifts to the air, dressings, and what touches tissue | Turned vague hospital “bad air” fears into a focused plan |

| carbolic acid (phenol) as a chemical tool | Soaked pads and treated dressings used on compound fractures | Brought a workable disinfecting method to real patients |

| Case reporting in the Lancet (1867) | Clear numbers: 11 cases, with outcomes recorded and compared | Gave other surgeons a reason to try the same infection control approach |

Lister’s Innovations in Surgical Procedures

Joseph Lister quickly moved from just treating cuts to making the whole room clean. He made antiseptic surgery a routine that could be improved.

He looked at everything that could touch the wound. This included who touched the tools and what was in the air. His curiosity made his approach feel new and possible.

Sterilization of Instruments

Lister went beyond the obvious in sterilization. He focused on everything that could touch the wound. He used carbolic acid because it worked well.

He suggested washing hands and tools with a 5% carbolic acid solution. He also warned against using porous handles, as they could trap dirt.

In 1867, he made a big change. He applied carbolic acid to wounds during surgery and covered them with an antiseptic paste. He shared these steps at a British Medical Association meeting in Dublin.

Then, he started using a spray to mist the operating room. From 1871 to 1887, he used a 1:100 dilution to fight germs in the air. He tried different spray devices, including a steam one.

| What Lister targeted | How it was handled | Why it mattered for surgical hygiene |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical instruments | Washed before and after use; attention to hard-to-clean parts and handles | Cut down the chance of carrying contamination straight into tissue |

| Surgeon hands | Washed with a 5% carbolic acid solution as part of the routine | Helped make clean hands a habit, not an afterthought |

| Patient skin and wound surface | carbolic acid used as a lotion during the operation, not only afterward | Reduced exposure at the moment the wound was most open and vulnerable |

| Sutures and dressings | Managed with antiseptic materials; antiseptic paste placed over the sutured wound | Lowered risk during healing, when infection often took hold |

| Operating room air | 1:100 spray mist used across the room during the procedure (1871–1887) | Matched the belief that airborne germs could land in the wound |

Aseptic Techniques vs. Antiseptic Techniques

Antiseptic surgery kills germs when they’re thought to be present. Aseptic technique blocks germs from getting in. Lister used antisepsis but moved towards asepsis.

Once you focus on sterilization and clean handling, you think in “keep it sterile” terms. This shift changed surgery’s feel in the room.

Lister’s Impact on Surgical Safety

Imagine a hospital ward in the 1800s. It could be a place of healing or danger. Joseph Lister’s push for cleanliness changed everything. He made infection control a planned effort, not just a fear.

When people call him the Father of modern surgery, it’s because of his impact. Cleaner methods let surgeons do harder operations with less fear. This led to big changes in bacteriology and wound care.

Reduction in Infection Rates

Before Lister, wound sepsis and gangrene were common. His antiseptic routine aimed to stop these problems. This led to fewer foul wounds and fewer deaths after surgery.

One example that stuck was his compound fracture cases. 9 out of 11 healed without infection. This made infection control seem real and repeatable, not just luck. Over time, reports showed antiseptic practice reduced ward fever and “hospital disease.”

| What surgeons watched for | Common before antiseptic routines | What improved as Lister-style habits spread |

|---|---|---|

| Wound sepsis | Suppuration and breakdown were treated as normal risks | Cleaner wounds and more predictable healing with stronger surgical hygiene |

| Gangrene | Feared complication that often followed injury or surgery | Less frequent progression when infection control became routine |

| Amputation pressure | Often used as a last-ditch move to outrun spreading infection | Less urgency to amputate when wounds stayed cleaner |

| Post-op survival | Deaths after surgery were commonly tied to infection | Lower mortality as antiseptic handling improved outcomes |

Changes to Medical Education

Lister taught by example, not just papers. He turned the operating room into a classroom. Students learned by watching, not just hearing.

Historian Michael Worboys says Lister’s calm example was key. It made surgical hygiene seem like a standard, not a quirky choice. Lister showed what it meant to be a modern surgeon.

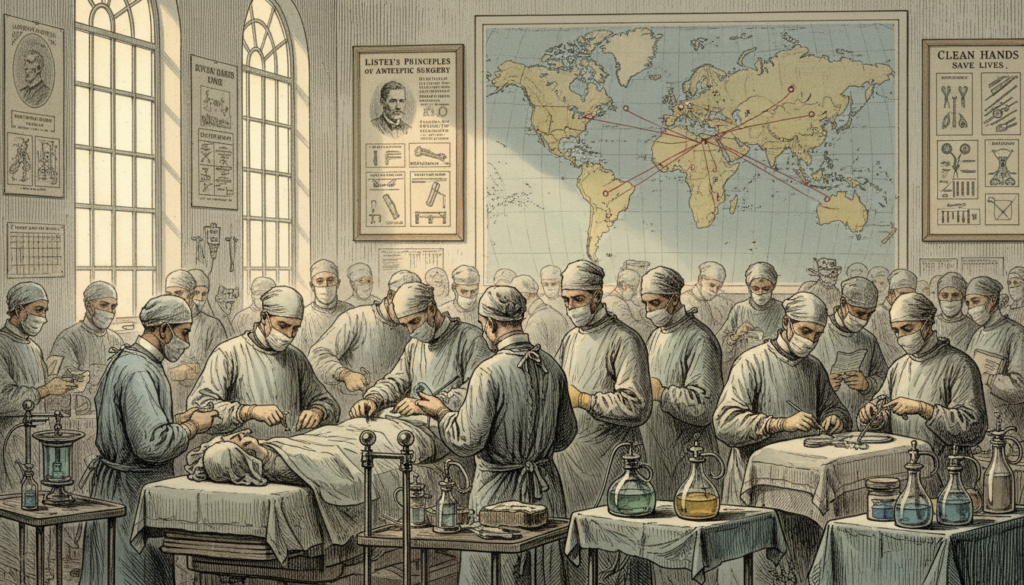

The Antiseptic Revolution’s Global Spread

Joseph Lister’s ideas quickly spread across hospitals. It was like a small-town gossip, moving fast through stories and demos. People argued a lot in surgical theaters.

But antiseptic surgery didn’t spread smoothly. Sometimes, doctors followed the carbolic acid rules well. Other times, they skipped them, making infection control seem like a hassle.

Adoption by Surgeons Worldwide

Doctors who trained with Joseph Lister or saw him work often adopted his methods. They talked about cleaner wounds and less “ward stink.” They also mentioned dressings that worked well.

But, antiseptic surgery was tricky. It needed careful timing, clean tools, and steady hands. If doctors used carbolic acid carelessly, infection control could fail.

- Direct observation helped: seeing the method done well made it easier to copy.

- Inconsistent routines hurt: partial use made results confusing and fed doubts.

- Local hospital culture mattered: busy wards and old habits could overrule new rules.

Case Studies in Different Countries

In the United States, many doctors doubted Joseph Lister’s methods by 1881. When President James Garfield was shot, doctors used unwashed hands and unsterilized tools. This was exactly what Listerism aimed to stop.

Garfield lived for 11 weeks after the shooting. His care showed the uneven state of infection control. It also highlighted how hard it is to change medical practices.

And then there’s the American twist. Listerine, named after Joseph Lister, came out in 1879 as a mouthwash. It was 54 proof. While hospitals debated Listerism, stores were already selling “antiseptic” products.

| Place and moment | What spread (or didn’t) | What it says about the era |

|---|---|---|

| Britain and European teaching hospitals | Listerism shared through demonstrations, surgical notes, and apprentices who copied antiseptic surgery step by step | Hands-on proof mattered more than slogans; routines traveled with people, not just papers |

| United States, 1881 (President James Garfield’s treatment) | Limited trust in Joseph Lister’s system; wound probing with unwashed hands and unsterilized instruments | Infection control depended on daily habits, and old habits stayed powerful even in high-profile care |

| United States, 1879 (Listerine launch) | “Antiseptic” adopted quickly in consumer culture; mouthwash marketed under Lister’s name (54 proof original formula) | Commercial speed didn’t match hospital change; antiseptic surgery and everyday products moved on different tracks |

Challenges and Criticisms of Lister’s Methods

Listerism didn’t catch on fast. It faced real challenges in operating rooms. These rooms were busy and hard to change.

Resistance from Peers

Many surgeons were not against science. They were practical. Lister’s methods added time and steps to surgery, which some found too much.

They wanted to see results. But, proving the method worked was hard. Some doubted it because of uneven results.

There was also a trust issue. People wanted to see proof in their own wards. But, opinions on infection causes varied, making agreement hard.

Then, there was the “air problem.” Lister wanted to clean the room, not just the wound. Many thought this was just show, even when it was meant to fight unseen dangers.

Common Misunderstandings

One big problem was when people didn’t follow the routine well. Skipping steps or not cleaning enough could ruin the whole thing. This made Listerism seem unreliable.

Carbolic acid had its downsides too. It could hurt and irritate, needing constant adjustments. Some patients got sick from it, making the method seem too harsh.

| What people expected | What often happened in practice | Why critics pushed back |

|---|---|---|

| Quick wins with Listerism after one change | Only parts of the routine were used, and steps were mixed or skipped | Infections were not gone, so the system looked overhyped |

| Carbolic acid would be a simple, safe cleaner | Skin and tissue irritation showed up, with strong solutions | Pain and damage made the approach seem risky |

| Cleaner air would mean fewer infections | Sprays were hard to control and easy to use unevenly | The “air problem” seemed vague and hard to measure |

Lister’s Legacy in Modern Medicine

Step into a modern operating room and you’ll notice something right away. The air is clean, and everything is sealed. This is all thanks to Joseph Lister’s idea of keeping microbes out.

Today, teams focus on being super clean and following strict routines. They don’t rely on old chemical sprays anymore. The main idea is simple: fewer germs mean fewer infections.

Continued Relevance of Antiseptic Practices

In hospitals, you see Lister’s work in the little things that matter a lot. Hand washing, sterilized tools, and careful wound care are key. Hospitals watch these closely because infections can spread fast.

And Lister’s influence didn’t just stay in books. Listerine, made in 1879, shows how his ideas reached everyday life. It’s a reminder of his lasting impact.

Honoring Lister: Awards and Recognitions

By the end of his career, Lister had earned many honors. He was President of the Royal Society from 1895 to 1900. This respect came from his big impact on surgery.

| Recognition | Year | What it signaled about his impact |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Medal | 1880 | His work pushed infection control from theory into daily practice. |

| Cameron Prize for Therapeutics | 1890 | Antiseptic thinking shaped treatment choices, not just surgery. |

| Albert Medal | 1894 | Public-facing value: safer care that mattered beyond the hospital. |

| Copley Medal | 1902 | A capstone honor for science with lasting medical results. |

It’s amazing how you can see Lister’s legacy everywhere. From sterile drapes to Listerine, it’s all about keeping things clean. This way, healing can happen without too many problems.

The Evolution of Surgical Practices Post-Lister

After Joseph Lister, the operating room got a lot cleaner and smarter. The main idea was simple: stop germs early. This idea is key in keeping surgeries safe today, even with new tools.

In Lister’s time, antiseptic surgery used carbolic acid a lot. Later, teams kept the goal but used better methods. They focused on keeping things clean from the start.

Advancements in Technology

Lister’s early sprayers evolved into better tools. Surgeons wanted something that worked well in real surgeries. Tools changed to be more reliable and easy to use.

But, carbolic acid spray was tough to handle. It made things harder for surgeons. Hospitals had to change how they worked to make things better.

Integration of Modern Sterilization Techniques

Over time, the focus shifted from just using chemicals to making everything sterile. Antiseptic surgery became part of a bigger system. This made keeping things clean seem easier and more routine.

| What changed | Earlier approach (chemical-heavy) | Later approach (system-driven) |

|---|---|---|

| Main strategy | Kill microbes on contact using carbolic acid | Prevent microbes from entering the wound through sterile technique |

| Instruments and dressings | Disinfected before use, sometimes repeatedly during a case | Heat-sterilized, wrapped, stored, and opened only when needed |

| Operating space | Sprays, wiped surfaces, and chemical-treated materials | Controlled setup, clean traffic patterns, and standardized surgical hygiene steps |

| Team habits | Skill varied by surgeon and local custom | Checklist-like routines that support consistent infection control |

Looking at today’s operating rooms shows Lister’s lasting impact. We aim to protect wounds just like he did. But now, we have smoother systems and fewer carbolic acid clouds.

Conclusion: The Importance of Lister’s Work Today

It’s amazing how surgery used to be a big risk. Before Joseph Lister, doctors worked in dirty conditions. They even thought pus was a good sign.

Then Lister used Louis Pasteur’s germ idea. He focused on keeping wounds clean. And things started to get better.

What’s important isn’t just the idea. It’s the proof. Lister showed that cleaning wounds and tools could save lives. This idea became known as Listerism.

Today, when you see a surgeon clean up, you see Lister’s work. We’re not doctors, but we get the main idea. Infection control is key because it stops infections from happening.

Joseph Lister passed away on February 10, 1912. But his work lives on. His ideas about keeping things clean are used in surgery and hospitals today. He’s known as the Father of modern surgery. His big lesson is that safer medicine means fighting infection.

FAQ

Why have you probably benefited from Joseph Lister even if you’ve never heard his name?

Who was Joseph Lister (the human version, not the statue)?

Where was Joseph Lister born, and what was his family background?

How did Joseph Jackson Lister’s microscope work influence Joseph Lister?

Where did Lister study medicine, and what were his early career milestones?

What was surgery like before Lister’s antiseptic revolution?

What did doctors think caused infection before germ theory caught on?

How dangerous were hospital infections in Lister’s time?

What were “hospital gangrene” and “ward fever,” and why did they scare surgeons?

How did Louis Pasteur’s germ theory shape Lister’s thinking?

What was Lister’s big leap about wound putrefaction?

Why did Lister choose carbolic acid (phenol) for antiseptic surgery?

What happened in Lister’s famous early compound fracture case?

What were Lister’s results from 1865 to 1867, and why did they matter?

What did Lister publish in The Lancet in 1867?

Did Lister only treat wounds, or did he redesign the whole surgical routine?

What changed in Lister’s protocol in 1867?

What was the carbolic spray, and why did Lister use it?

What’s the simple difference between antiseptic and aseptic technique?

How did Lister’s ideas reduce infection and amputations?

How did Lister’s ideas change medical education and convince other surgeons?

Did Lister’s antiseptic methods spread worldwide right away?

Why were some surgeons resistant to Listerism?

What were common misunderstandings that made Lister’s system fail in other hands?

What were the downsides of carbolic acid in surgery?

What does President James Garfield’s 1881 case reveal about U.S. adoption of antiseptic surgery?

Why is Listerine connected to Joseph Lister?

Why is Joseph Lister called the father of modern surgery?

What honors did Lister receive for his medical breakthroughs?

How did surgical practice evolve after Lister’s early antiseptic approach?

What parts of Lister’s approach are used in modern operating rooms?

Get More Medical History

Join our newsletter for fascinating stories from medical history delivered to your inbox weekly.

The History of Healing

The History of Healing