Galen’s Influence on Medicine for Over 1,000 Years

Explore how Galen, the eminent Greek physician, shaped the course of medical practice and theory with his groundbreaking work for over a millennium.

Galen’s ideas in medicine lasted over 1,000 years. That’s longer than from the Magna Carta to your last doctor visit. It makes you wonder how one person’s ideas became the standard for so long.

Medicine loves looking back (and you’ve seen it). Your doctor’s form asks about your family, past symptoms, and surgeries. We look at your history because it helps us today.

Before medicine was organized, treatments were rough. Trepanation was one, where people cut holes in skulls for headaches and more. Ancient Peru is known for skulls with up to five holes, showing some patients survived.

And it gets even stranger. They sometimes covered the holes with gourd or gold. In Europe, the removed bone was even worn as an amulet. Trepanation was even in art, like in Hieronymus Bosch’s work from 1494.

Galen of Pergamon brought order to medicine. He had a clear story about the body, why it gets sick, and how to fix it. His ideas were easy to teach and follow, making him a key figure in medicine for centuries.

Key Takeaways

- Galen helped shape the Influence on medicine for more than a millennium.

- Medical history is important because it affects today’s care.

- Trepanation shows early treatments were intense and experimental.

- Ancient Peru’s skulls prove trepanation worked and was repeated.

- Trepanation was in European art, from Bosch to the 16th century.

- Galen of Pergamon offered a clear system when medicine was chaotic.

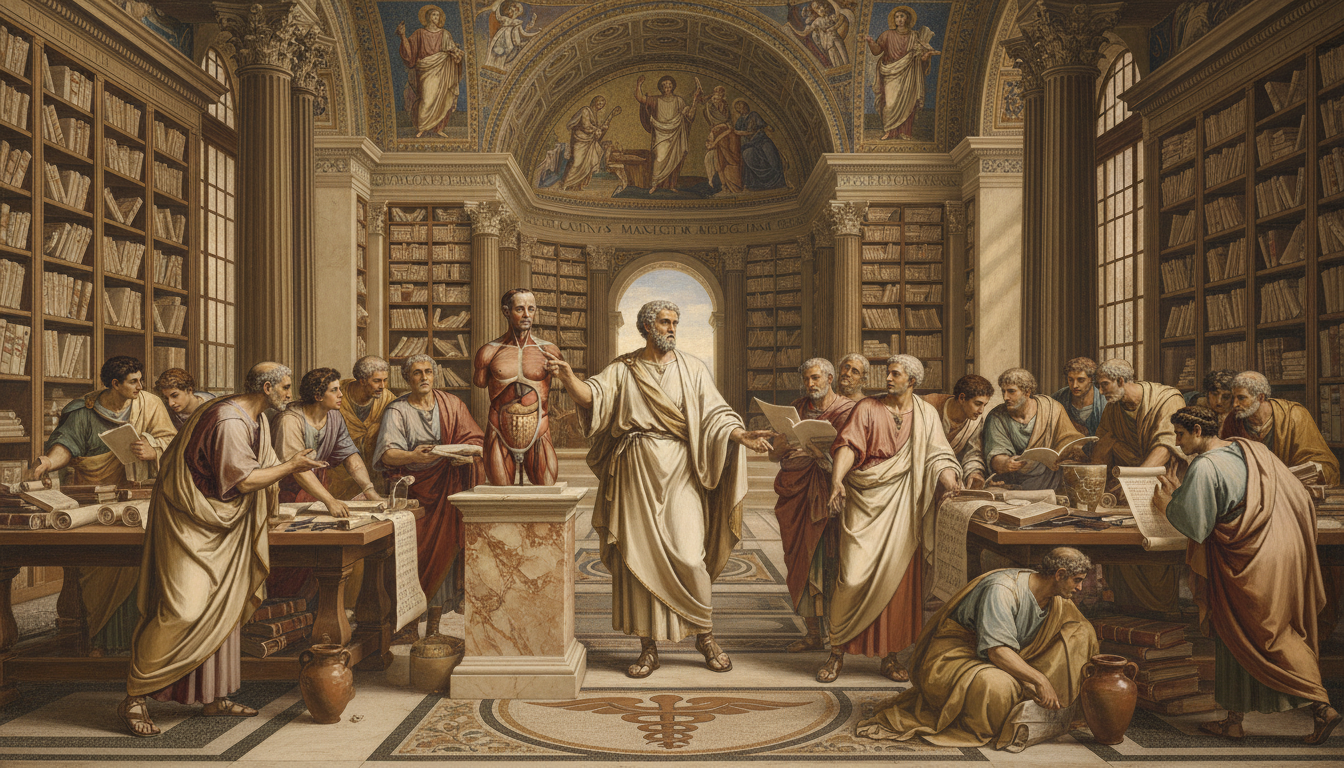

Introduction to Galen and His Legacy

Galen’s name is often linked with “old-school medicine.” This Ancient physician didn’t just treat patients. He left behind a huge written record that people copied, debated, and used for ages.

In his time, people wanted medical answers that felt solid. They wanted something organized, repeatable, and convincing. A Greek physician like Galen could argue his case with confidence.

By the time Galen arrived, the Roman Empire was huge. Ideas traveled fast, teachers competed, and reputations spread quickly. Galen’s legacy began in this mix of ambition, learning, and public attention.

Who Was Galen?

Galen (130–200 C.E.) was born in Pergamum, a city that valued healing. There was a famous statue of Asclepius, and Galen openly described his devotion to that healing god.

Pergamum also had a major library that rivaled Alexandria. Galen grew up surrounded by books and debate. His father, Nicon, was a successful architect who paid for a wide education—math, grammar, logic, and philosophy.

Galen didn’t just stick to one camp. He studied many philosophies, then leaned into what worked. This practical mindset suited a Greek physician trying to build a method, not just win arguments.

He also wrote constantly. Scholars estimate that about 10% of all surviving ancient Greek literature comes from him. For an Ancient physician, that’s a huge paper trail that shaped what later readers thought medicine was.

The Historical Context of His Work

Galen entered a medical world that was both sharp and hands-on. The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BC) shows 48 trauma cases from head to torso.

It uses close observation: visual and smell clues, palpation, and pulse-taking. It even includes the first known written use of the word brain, along with notes on the meninges, brain surface, cerebrospinal fluid, and intracranial pulsations.

But Egypt also used amulets and spells, and other texts like the Ebers Papyrus leaned hard into magic. So you can see the tension: careful casework living right next to supernatural fixes. A Roman physician like Galen inherited that messy blend, even if he didn’t always advertise it.

Rules and money shaped medicine, too. The Code of Hammurabi had 282 laws, and 17 focused on physicians, with fees and punishments tied to outcomes.

| Source | What It Shows | Concrete Details | Why It Matters for Galen’s Era |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BC) | Medicine could be surprisingly practical and case-based | 48 trauma cases; organized head-to-torso; observation, palpation, pulse-taking; early use of “brain”; notes on meninges and cerebrospinal fluid | Sets expectations for careful observation that an Ancient physician could claim as “real medicine” |

| Ebers Papyrus (ancient Egypt) | Healing often blended remedies with magic | Strong focus on spells and ritual alongside treatments | Shows the background noise of superstition a Greek physician had to compete with in public life |

| Code of Hammurabi (282 laws) | Medical work was regulated with high stakes | 17 physician laws; saving a noble with a bronze lancet paid 10 shekels; killing him could mean a hand cut off; focused on surgery | Explains why a Roman physician would want authority, clear rules, and a reputation for skill |

So when Galen starts writing and teaching, he’s not inventing medicine from scratch. He’s walking onto a stage already packed with case notes, traditions, fear of failure, and public pressure—exactly the kind of world that rewards a bold system-builder.

Galen’s Contributions to Anatomy

Ever wonder how ancient doctors figured out what was inside the body? Galen played a big role in that. As a Medical philosopher, he didn’t just stick to old ways. He encouraged his students to observe closely, test ideas, and keep detailed notes.

This approach became key to Galenic medicine. It made his anatomy writings useful for teaching, not just interesting to read.

Dissection and Observation Techniques

Galen’s method started with watching, then explaining. This style, called critical empiricism, is powerful for Medical practice. It involves observing the body, forming theories, and checking them against evidence.

Because human dissection wasn’t always possible, he used animals like monkeys. This method allowed him to study muscles, nerves, and organs in detail.

In Alexandria, Galen taught students to see bones directly. He said it was easy because doctors used autopsy for teaching. Whether he dissected humans himself is debated, but Alexandria’s culture helped Galenic medicine trust the eye.

Key Anatomical Discoveries by Galen

One big achievement was his first drawing of the four-chambered heart. It shows how careful description can last for centuries.

He also tried to explain why veins and arteries look different. In On the Use of the Parts, he believed Nature doesn’t waste anything. So, he thought arteries carried blood mixed with pneuma, while veins carried regular blood.

He also noticed tiny, almost invisible vessels connecting the two systems. Some of his ideas were sharp observations, others were a bit off. But for a Medical philosopher, it created a map for students to follow in Medical practice.

| What Galen Studied | What He Noticed | How It Shaped Galenic medicine | Why It Mattered for Medical practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative dissection (specialy primates) | Similar layouts of organs, muscles, and major vessels across species | Made anatomy feel learnable through side-by-side comparison | Gave students a repeatable way to build skill when human bodies weren’t available |

| The heart and major vessels | A four-chamber structure described clearly enough to teach | Anchored later lessons on circulation concepts, even before modern physiology | Helped doctors talk about symptoms in a more organized, body-based way |

| Veins versus arteries | Different wall thickness and structure suggested different roles | Supported the “Nature does nothing in vain” approach in anatomy | Encouraged observation-driven reasoning in bedside Medical practice |

| Tiny vessel connections | Proposed near-invisible links between blood systems | Kept the model coherent and teachable for centuries | Let learners imagine hidden pathways without needing advanced tools |

The Four Humors: Understanding Health

If you’ve ever heard someone called “hot-blooded” or “melancholic,” you’ve seen an old medical idea. Galen’s theories turned this idea into a system doctors used at the bedside. In Galenic medicine, your health story was about your internal mix, not just symptoms.

The humor model lasted for centuries because it connected diet, weather, sleep, mood, and pain. It wasn’t just about fluids. It was a way to see the world every day.

What Are the Four Humors?

The four humors were phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile. They were like four basic ingredients your body managed. In Galenic medicine, each humor had a personality: warmth, cold, dryness, or moisture.

Galen’s theories tied these humors to body centers, making the system feel mapped and physical. Phlegm was linked to the head, blood to the heart, black bile to the liver, and yellow bile to the gall bladder. This setup made it easy to explain health issues.

| Humor | Body “Center” in the Model | Common “Feel” People Expected | Everyday Clues Doctors Looked For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phlegm | Head | Cool, sluggish, heavy | Sleepiness, congestion, slow recovery |

| Blood | Heart | Warm, lively, bold | Flushed skin, strong pulse, restlessness |

| Black bile | Liver | Dense, stuck, serious | Low mood, poor appetite, lingering aches |

| Yellow bile | Gall bladder | Sharp, irritated, heated | Digestive upset, bitter taste, quick anger |

Galen’s Theory of Balance

Balance meant health; imbalance meant illness. This simple rule was a big reason for the lasting influence of Galen’s medicine. If you felt off, something was out of balance.

Galen’s thinking was also influenced by Plato’s idea of a three-part soul. The head was linked with reason, the heart with spirit and emotion, and the liver with desire. This made the humor model feel complete, linking body and mind.

Once you understood this logic, treatments made sense. Too much blood could mean too much heat and emotion, so bloodletting was a common treatment. Galenic medicine aimed to correct imbalances with food, rest, baths, and sometimes more intense measures.

Ancient Ayurveda in India also saw illness as a disturbance of key substances. Ideas like these may have traveled and blended, explaining the influence of Galen’s medicine in more than one tradition.

Galen’s Influence on Medical Education

Ever wonder how a Medical practice gets “official”? Follow the paper trail. Galen of Pergamon didn’t just heal people. He helped set what students should learn, in what order, and with what tools.

His influence shows up in clinics and classrooms. It shapes how medicine is taught for ages.

Establishing Medical Schools

In Alexandria by the 6th century, teachers faced a problem. Galen of Pergamon wrote so much. Students couldn’t just “read Galen” and call it a day.

So, educators built a structured course from his work. They called it The Sixteen Books. It actually pulled together 24 treatises or extracts.

| Curriculum Area | What Students Focused On | Why It Mattered in Training |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomy | Body structures and how parts connect | Gave students a shared map for exams, lectures, and hands-on study |

| Physiology | How the body functions in daily life | Helped link symptoms to body processes instead of guesswork |

| Pathology | What changes when illness hits | Made disease something you could describe and debate with clear terms |

| Therapeutics | Treatments, timing, and expected effects | Turned bedside choices into steps you could explain and defend |

| Hygiene | Cleanliness, routines, and prevention | Showed that health wasn’t only about cures; it was also about habits |

| Dietetics | Food, drink, and lifestyle adjustments | Kept care practical and affordable for many patients |

This Alexandrian package was read in a set sequence. It included lectures and commentaries. For students, it created a steady pipeline: learn the basics, argue the details, then apply it at the bedside.

Methods of Teaching Medicine

Galen of Pergamon cared a lot about being read “the right way.” He even wrote guides for it, like The Order of My Own Books, plus advice tucked into the final chapter of Art of Medicine.

He also made summaries and abridgments. This mattered if you had less background—or less money. It made Medical practice feel less like a private club and more like a skill you could train for.

And then there’s the authenticity drama. After overhearing an argument over which texts were real, the Ancient physician wrote My Own Books, an annotated list meant to sort genuine work from copycats.

Even so, forged “Galen” texts kept floating around. Later readers had to stay sharp. Education became more than lectures. It was also learning how to judge sources, follow a trusted reading order, and build medical habits from a curated shelf.

Galen’s Works and Publications

Following Galen through his writing, you feel the ancient medical world’s fast pace. He was not just a doctor but a Medical philosopher. He wanted medicine to make sense as a whole, not just a bunch of tips.

His books were important. They traveled well, argued hard, and gave readers a framework to follow. In an era without journals or labs, repeating a framework was powerful.

“On the Natural Faculties”

On the Natural Faculties shows Galen building a connected story about how bodies work. He sees the body as a system with jobs to do—taking in food, changing it, moving it, and keeping you alive.

He also argues a lot. Galen challenges Erasistratus and his followers, pushing back on their neat theories that ignore what careful eyes can see. The debate is clear: how much should you trust a clean idea, and how much should you trust what you can actually observe?

Galen’s approach is a mix. He uses observation to keep his theories grounded, but he also wants a strong model that ties everything together.

Impact of “On Healing”

On Healing is part of a bigger writing habit. Galen wrote treatises, case-based discussions, and sharp polemical arguments. Some were for working doctors, others for curious readers.

He didn’t just stick to medicine. As a Medical philosopher, he also wrote on philosophy, textual commentary, and even linguistic work tied to Greek comedy. This range made his voice familiar across different libraries and readers.

After the fire of 192 CE damaged his library, survival became part of the story. Galen had already pushed for copies—shared with friends and placed in libraries—so the work didn’t depend on one room or one shelf. Some pieces even turned up again later, including texts he thought were gone.

Before modern labs and publishing, what survived was what counted. Galen’s careful copying habits helped his books last, and his theories gained authority because they were the ones people could read and argue with.

| What you notice in the texts | How Galen uses it | Why it helped the books last |

|---|---|---|

| Big, linked explanations of body functions | Builds a full model you can apply across symptoms and organs | Readers can teach it, summarize it, and pass it on without losing the core idea |

| Direct debates with rivals like Erasistratus | Tests claims against observation and pushes back on weak logic | Argument-driven writing is memorable, easy to quote, and hard to ignore |

| Many formats: treatises, case-style notes, and polemics | Reaches both clinicians and general readers with different needs | More audiences means more copies, more circulation, and more chances to survive |

| Active copying and sharing before the 192 CE fire | Spreads manuscripts through friends and library collections | Redundancy protects the work when a single collection is damaged or lost |

Influence on Medieval Medicine

Imagine a relay race with fragile manuscripts as the baton. That’s how Galen kept his work alive after the Western Roman Empire fell. In the Latin-speaking West, many turned away from Greek texts. But the story didn’t end there.

In Byzantium, scholars kept copying, editing, and teaching Galen’s writing in Greek. They used a practical study set called the “Sixteen Books.” This made Galenic medicine something you could learn, not just admire.

How Galen’s Ideas Were Preserved

Over time, Galen’s works traveled through translation chains. A text might go from Greek to Syriac, then Arabic, then Hebrew, and lastly Latin. Each step helped spread the Influence on medicine, even when the original Greek was hard to find.

These chains also shaped how people understood Galen. Translators didn’t just swap words; they clarified terms, fixed errors, and sometimes argued over meanings. Medieval readers often met Galenic medicine through these careful, human choices.

- Byzantium kept Greek manuscripts alive through steady copying and teaching.

- The “Sixteen Books” made Galen easier to study in a classroom setting.

- Multi-step translations carried the Roman physician into new languages and regions.

Integration in Islamic Medicine

Now zoom east to the translation movement. The “Sixteen Books” were translated into Syriac by about 550 CE and into Arabic by the 10th century. From there, Galenic medicine became a core part of medical training across the Islamic world, including Christian and Jewish communities.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873), a Christian physician in Baghdad, was a key force here. He listed 129 works by Galen translated into Syriac and Arabic, often by him or his circle. He also described the real-world grind of the job: sponsors, methods, and the hunt for Greek manuscripts that weren’t always easy to track down.

Later thinkers built on that foundation in different ways. Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037) organized Galen’s ideas into a system that students could follow. Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) engaged with Galen closely and pushed back where observation demanded it, which kept the Influence on medicine lively instead of frozen.

| Milestone | Where it happened | What moved forward | Why it mattered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek manuscripts kept in circulation | Byzantium | Core writings of the Roman physician | Preserved a working Greek text base for later translators and teachers |

| “Sixteen Books” study framework | Alexandria and later teaching hubs | Teachability of Galenic medicine | Made an enormous body of work manageable for students and instructors |

| Syriac translations (by ~550 CE) | Syriac-speaking scholarly communities | Key medical vocabulary and commentary | Created a bridge language that helped texts travel and stay consistent |

| Arabic translations (by the 10th century) | Baghdad and the wider Islamic world | Medical curricula and reference texts | Expanded the Influence on medicine through libraries, hospitals, and classrooms |

| Hunayn ibn Ishaq’s translation network | Baghdad | Cataloging and translation practice | Tracked 129 Galen works and stabilized how Galen was read in new languages |

| System-building and debate | Centers of learning from Persia to the Levant | Ibn Sina and Ibn al-Nafis engaging Galen | Kept Galenic medicine active through organization, critique, and refinement |

Galen’s Role in the Renaissance

Imagine scholars in crowded libraries, searching for the most accurate pages. This is what happened when Galen of Pergamon returned to Western Europe. It was like a rush to find the right parchment.

For a long time, Galen was known only through others. But when texts started moving again, finding “the real Galen” became a big deal.

Reviving Galenic Medicine

In the 11th century, Galenic medicine came back to the Latin West. It was through Latin translations from Arabic versions. These works were copied, debated, and taught as if they were essential.

By the mid-13th century, universities were teaching medicine based on these translations. Montpellier was a key place, with Italy and Spain also involved. If you were studying to be a doctor, Galen was a big part of your studies.

The Renaissance made things even more exciting. More people could read Greek, and they wanted the original texts. After the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, Greek scholars and manuscripts came to Western Europe. This led to a lot of comparing and correcting.

By the 15th century, scholars were checking translations against the Greek originals. They found mistakes, like mistranslations and copying errors. This didn’t make Galen less important; it made his name even bigger, as everyone had something to correct and debate.

| Renaissance moment | What changed in access to Galen | Why it mattered for medical study |

|---|---|---|

| 11th-century translation wave | Latin versions arrived mainly through Arabic pathways | Galenic medicine became teachable again in Western classrooms |

| Mid-13th-century university uptake | Latin translations from Arabic and Greek circulated widely | Programs at Montpellier and schools in Italy and Spain used Galen of Pergamon as core reading |

| 1453 and the movement of manuscripts | Greek scholars and texts traveled west after Byzantine political collapse | Students and professors could check claims against original Greek sources |

| 15th-century correction culture | Side-by-side comparisons revealed errors and confusion in older copies | The Greek physician became a focus for editing, commentary, and sharper argument |

Impact on Notable Renaissance Thinkers

A big event happens in Venice: the Aldine Press prints the first complete Greek edition of Galen’s works in 1525. It’s edited by Joannes Baptista Opizo and Andreas Asulanus. Suddenly, Galen’s works are available on a large scale.

This access changes how readers think. Galenic medicine is now easier to study and challenge. The mid-16th century is buzzing with excitement: everyone wants to read Galen in his own language.

But there’s a twist. Anatomy texts that were unknown for ages spark new research. This research makes people question old anatomical claims. Galen becomes the key that makes new work urgent.

Critiques and Challenges to Galen’s Ideas

Galen’s system was neat and complete, so doctors used it for a long time. His theories gave doctors a shared language. This helped the Influence on medicine spread across regions and schools. But, once you’ve got a big, tidy story, it can start answering questions a little too fast.

Over the centuries, more physicians started asking a blunt question: what do we actually see happening in the body? That’s where the pressure built. When observation didn’t match the old explanations, the confidence in Galen’s theories began to wobble, even inside everyday Medical practice.

The Shift to Empirical Evidence

Think of it like a slow-motion breakup between theory and observation. Galen’s approach tried to do both: careful looking, plus a framework that made the details feel meaningful. That balance powered the Influence on medicine because it was teachable and easy to pass on.

But, some claims didn’t age well. The idea that blood was made and then used up by tissues, moving in one direction, started to look shaky. The same went for the claim that arteries carried blood mixed with pneuma. As methods improved, Medical practice began to demand proof you could repeat, not just explanations that sounded right inside Galen’s theories.

| Pressure Point | What Galen’s system emphasized | What later observers pushed for | Why it mattered for Medical practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| How to judge a claim | Fit with an overall theory | Results you can verify with observation | Changed what counted as “good” evidence in clinics and classrooms |

| Blood movement | One-way flow; blood produced and consumed | Closer tracking of circulation and vessel function | Forced revisions that reshaped the Influence on medicine over time |

| Arteries and pneuma | Blood plus pneuma as a key explanation | More direct testing of what vessels actually contain | Reduced reliance on elegant stories when facts didn’t match |

| Authority in learning | “Galen says so” as a shortcut | Check the text, check the body, check the results | Made Medical practice less dependent on reputation alone |

Notable Figures Who Challenged Him

Some of the most interesting pushback came from inside the tradition, not from people trying to burn it down. Ibn Sina (Avicenna) organized and refined earlier medical writing, and he didn’t treat Galen’s theories as untouchable. In his hands, the Influence on medicine looked more like a living toolkit than a museum piece.

Ibn al-Nafis went further and challenged specific ideas about how the heart and lungs work. That kind of critique mattered because it wasn’t just arguing; it was trying to make Medical practice match the body more closely.

Later, Renaissance scholars revisited Greek originals and noticed how much could go wrong in transmission. Copying errors and mistranslations weakened blind trust, because even a strong system can get warped on the page. That didn’t erase Galen’s theories overnight, but it changed the tone: the Influence on medicine became less about repeating and more about checking.

- Inside-the-system critiques kept familiar methods but questioned weak spots.

- Better texts exposed how errors could sneak into “standard” teachings.

- Rising standards made Medical practice feel more like testing than reciting.

Galen’s Enduring Influence on Modern Medicine

Galen feels close today, not because we follow all his old claims. But because his ways are seen in how we talk about symptoms and look for patterns over time.

Exploring a Medical philosopher’s work is fun. You start to notice small reminders of them in our daily Medical practice. These reminders don’t always show where they came from.

How Galenic Principles Persist Today

Galen’s big idea is that each patient is unique. He pushed for careful attention to each case. Today, we see this when a guideline doesn’t fit a real person.

Modern medicine uses protocols, but also judgment. Your story, timeline, past labs, and meds are all important. They help us understand what’s changed.

History-taking is another Galenic idea that lives on. We treat a patient’s past as valuable data, not just trivia. This mindset is seen when we ask, “When did this start?” and follow the trail.

- Case focus: listening for the detail that makes you you, not just “a typical patient.”

- Pattern spotting: comparing today’s signs with what’s been recorded over weeks or years.

- Notes as tools: using written records to support memory and sharpen decisions.

Galen’s Impact on Contemporary Practices

Galen’s influence lasted through training and textbooks, even after his explanations were outdated. Oxford University, for example, taught from Galenic texts into the 18th century. This is amazing to think about in a world that was already changing fast.

In the 19th century, Karl Gottlob Kühn published a huge collection of Galen’s writings. It was for curious historians and physicians who wanted useful insights for their practice.

Medicine didn’t fully move away from Galen’s ideas until about 150 years ago. So, when we debate “the evidence” versus “the patient,” we’re echoing an old argument. A Medical philosopher helped keep this debate alive.

| Where you feel it | What it looks like today | Why it matters in Medical practice | Galen’s long tail |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient story | Detailed history, symptom timeline, and follow-up questions | Builds context so care matches your real life, not a generic average | Galen treated prior events as clues that shaped the present |

| Individual vs. general rules | Guidelines balanced with clinician judgment for complex cases | Keeps care flexible when a standard pathway doesn’t fit | The Medical philosopher argued for close attention to the single case |

| Teaching tradition | Medical students read “classic” texts alongside modern research | Shows how ideas evolve, and why old errors can teach good habits | Oxford University lectured from Galenic material into the 18th century |

| Editing and reference culture | Large, organized editions used for study and comparison | Makes it easier to track how concepts change across time and authors | Karl Gottlob Kühn’s 19th-century edition kept Galen available to physicians |

Galen in Popular Culture

Galen of Pergamon is everywhere, not just in medical books. His name appears in art, stories, and the search for ancient wisdom. It’s fun to see how he became a character people wanted to see.

References in Literature and Media

In a medieval manuscript, Galen is shown with Hippocrates. The image is from Liber de herbis et plantis by Manfredus de Monte Imperiali. It’s from the 14th century and is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 6823.

Galen holds a scroll with a quote: “I mean to eat to live, while others live to eat.” It’s not a lab scene. It’s a staged moment that sells character.

In another image, Galen is with Plato and Aristotle. This is from Ibn Jazla’s Taqwīm al-abdān in the University of Glasgow’s library. Here, Galen is seen as a wisdom figure, not just a doctor.

| Artifact moment | What you see | What it signals about fame |

|---|---|---|

| Liber de herbis et plantis (Latin 6823) | Galen with Hippocrates; a scroll about eating to live | An Ancient physician framed as a moral voice, not just a healer |

| Taqwīm al-abdān frontispiece | Galen placed with Plato, Aristotle, and Hayqār Hakīm | Galen of Pergamon presented as “medicine’s sage,” part of a bigger canon |

Galen’s Legacy in Today’s Society

Galen’s name became so valuable that fake texts were made under it. Historians are trying to figure out what’s real. This shows how famous he was, even in ancient times.

In the United States, we treat some expert voices like brands. We argue about what’s real and what’s hype. We also look at old treatments like mummies and bloodletting, wondering if our own treatments will seem strange someday.

Conclusion: Galen’s Lasting Impact on Medicine

So why did Galen’s ideas last over a thousand years? He didn’t just guess. He watched, compared, and built big ideas from what he saw. His mix of philosophy and hands-on study is admired today.

Summary of His Contributions

Galen’s theories covered a lot. He used comparative anatomy and described the body in detail. He believed in a neat, unified logic: humors and contraries.

He wrote a lot, too. Scholars say it’s almost 10% of surviving ancient Greek literature. He organized copying and distribution. His work became the core of medical study.

What Can We Learn from Galen Today?

Galen’s story shows how medicine grows. It’s through bold observation and persuasive explanations. His work was kept alive by Byzantium and later by printing.

The best lesson is simple. Galen’s ideas show the value of organized thinking and real patient care. But, they also warn us about the dangers of incomplete evidence. Galen’s story is a big part of why modern medicine is what it is today.

FAQ

Why should you care about Galen’s influence on medicine today?

What’s a jaw-dropping example of early medicine before Galen’s system felt “orderly”?

Who was Galen, really?

Where did Galen come from, and why did it matter?

What kind of education shaped Galen’s thinking?

What was medicine like before and during Galen’s time?

What does the Edwin Smith Papyrus reveal about early medical observation?

How did superstition shape medicine in Egypt and beyond?

How did law regulate doctors in the ancient world?

Did Galen dissect human bodies?

Why is Alexandria important to Galen’s anatomy story?

What were Galen’s key anatomical discoveries?

What did Galen think arteries and veins carried?

What are the four humors in Galenic medicine?

How did Galen explain health and disease?

How did Plato influence Galen’s thinking about the body?

Why did bloodletting make sense in Galen’s system?

Did other cultures have similar ideas to the humors?

How did Galen shape medical education for centuries?

How did Galen try to control how people read him?

Why did Galen worry about forged texts?

What is “critical empiricism,” and why is it tied to Galen?

What were some major errors in Galen’s theories?

Who challenged Galen’s authority, and how?

How do Galenic principles show up in modern medicine?

How long did Galen remain influential in medical education?

Where does Galen appear in literature and visual culture?

Why did Galen’s name become a kind of “brand”?

What are the most important contributions of Galen of Pergamon?

What can you learn from Galen’s story without treating it like trivia?

Get More Medical History

Join our newsletter for fascinating stories from medical history delivered to your inbox weekly.

The History of Healing

The History of Healing