Edward Jenner and the Origins of Vaccination

Discover how Edward Jenner’s groundbreaking work led to the smallpox vaccine and laid the foundation for modern immunology.

Smallpox killed about 300 million people in the 20th century. That’s a huge number. If you live in the United States today, you’ve likely never seen smallpox. This is thanks to vaccines.

Smallpox was more than just a rash. It caused scars, blindness, and destroyed families for centuries. Vaccines changed how we deal with diseases. We started to prevent them instead of just treating them.

Edward Jenner wasn’t the first to think cowpox could fight smallpox. But he was the first to test it and share his findings. Francis Galton said science honors those who convince the world. Jenner convinced the world about vaccines.

Today, smallpox is talked about again because of national security. Looking back at the first smallpox vaccine is important. It shows how we protect ourselves from diseases.

Key Takeaways

-

Smallpox was one of the deadliest diseases in human history, even into the 1900s.

-

Edward Jenner helped turn a local observation into a repeatable medical method.

-

Vaccination history isn’t just about science—it’s about proof, persuasion, and public trust.

-

The smallpox vaccination reshaped public health by making prevention realistic.

-

Modern security concerns have kept smallpox on the radar, even after 2001.

-

This origin story explains why vaccines spark debate and why they’re important.

Who Was Edward Jenner?

Edward Jenner was a doctor who lived before vaccines were common. He was curious and noticed things others didn’t. People later called him the father of immunology, but he started as a regular doctor.

Early Life and Education

Edward Jenner was born on May 17, 1749, in Berkeley, Gloucestershire. His father was a vicar. When Jenner was 5, he lost his parents and moved in with his brother.

By his teens, he was learning medicine through apprenticeship. He worked with a surgeon in Sodbury near Bristol at 13. Later, he worked with George Harwicke, learning important skills.

At 21, Jenner went to London to study at St. George’s Hospital. He learned from John Hunter, a famous surgeon. They became close friends until Hunter’s death in 1793.

Contributions to Medicine

After studying, Jenner returned to Berkeley in 1773. He was known for his skills and kindness. Back then, people believed in the miasma theory, not germ theory.

Jenner didn’t just make house calls. He studied species from Captain Cook’s voyages. He even built a hydrogen balloon in 1784. His work was full of curiosity and tinkering.

He was also interested in natural history. His paper on cuckoos in 1788 made him a Fellow of the Royal Society. Later, photography proved his findings right.

Outside medicine, Jenner loved music and poetry. He collected specimens and watched wildlife. His curiosity and persistence were key to his success.

| Part of Jenner’s life | What he did | Why it mattered later |

|---|---|---|

| Early training | Apprenticed in the countryside (Sodbury area), gaining practical surgical and apothecary skills | Built comfort with real-world cases, where careful routines and cleanliness could change outcomes |

| London and mentorship | Studied at St. George’s Hospital and learned under John Hunter | Absorbed an experimental mindset that shaped how Edward Jenner tested ideas instead of just repeating tradition |

| Natural history work | Classified species from Captain Cook’s first voyage; studied birds and animal behavior | Strengthened his habit of close observation—key for a pioneering immunologist working without modern lab tech |

| Royal Society recognition | Published the 1788 cuckoo paper and became a Fellow of the Royal Society | Showed he could contribute original findings, supporting his later reputation as the father of immunology |

| Practical medicine at home | Returned to Berkeley in 1773, treated patients, joined local medical groups, and improved tartar emetic preparation | Kept his work grounded in community health needs, not abstract theory |

The Smallpox Epidemic

Before the smallpox vaccine, smallpox was a huge threat. It spread fast, caused a lot of harm, and left marks on people’s faces. It was one of the most feared diseases in history.

Historical Context of Smallpox

Smallpox first appeared around 10,000 BC in northeastern Africa. It spread to India through ancient trade routes. This was the start of a long journey of fear and death.

There’s evidence of smallpox on mummies from Egypt’s 18th and 20th Dynasties. Pharaoh Ramses V, who died in 1156 BC, shows signs of the disease. His remains have marks that look like smallpox.

Early writings mention smallpox in China as far back as 1122 BC. It also appears in ancient Sanskrit texts from India. By the time it reached Europe, it was a regular disaster.

Major movements of people helped spread smallpox. Arab expansion, the Crusades, and European voyages carried it across borders. In the Americas, it helped destroy the Aztec and Inca empires.

The language around smallpox tells a story. Bishop Marius of Avenches called it variola around AD 570. In late 15th-century England, it was known as “small pockes” to distinguish it from syphilis. By the 18th century, it was called the “speckled monster” in England.

Impact on Public Health

Smallpox didn’t just kill; it changed life. In 18th-century Europe, about 400,000 people died every year. Survivors often had deep scars.

Survivors also often went blind. This changed what “recovery” meant. The fatality rate was high, with some outbreaks killing up to 60% of those infected.

Spread was tied to power and conflict. During the French-Indian War, Sir Jeffrey Amherst suggested using smallpox against American Indians. The slave trade also spread it, mixing outbreaks in crowded, high-risk conditions.

| Public Health Pressure Point | What People Faced | Why It Mattered for Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Mass mortality | Roughly 400,000 deaths annually in 18th-century Europe | Communities demanded any tool that could reduce deaths from infectious diseases |

| Survival with permanent harm | Scarring was common; about one-third of survivors went blind | Risk wasn’t only death, so interest grew in variolation and later smallpox vaccination |

| Extreme risk for infants | Infant fatality reported near 80% in London and 98% in Berlin in the late 1800s | Families and officials focused on preventing childhood infection at any cost |

| Rapid spread through movement | Trade, war, and forced migration helped carry outbreaks across continents | Public health started to connect travel and crowding with outbreak control |

Discovering Cowpox

Here’s a weird clue from farm animals that changed everything. People noticed a pattern: if you got smallpox once, it often didn’t come back.

In dairies, another idea kept showing up—cowpox. It wasn’t just a theory. It was a rumor passed around with milk and sore hands.

By the time Edward Jenner was a young doctor, variolation was the main way to prevent smallpox. It involved using smallpox material on purpose. This was seen as the best option, even with risks.

Experiments with Cows

Edward Jenner heard a dairymaid’s bold claim during his training. She said if you had cowpox, you wouldn’t get smallpox. This idea stuck with him.

He wasn’t alone in his thoughts. Others had noticed the same pattern. Benjamin Jesty had even tested it in 1774. This shows Jenner was gathering clues, not making them up.

The Role of Cowpox in Immunity

Jenner thought, what if we could spread cowpox on purpose? This could be safer than variolation. This idea was the start of something big.

The old method of variolation and the new idea of cowpox are easy to compare. Here’s what people knew back then:

| What people used or noticed | How it worked (in plain terms) | Why it mattered to vaccination history |

|---|---|---|

| Variolation | Deliberate exposure to smallpox material to trigger protection | Common before 1796, but risky and hard to control |

| Farmworker folk knowledge about cowpox | Natural cowpox infection seemed linked with fewer smallpox cases | Everyday observations hinted at a safer path than variolation |

| Earlier trials by Benjamin Jesty (1774) | Testing cowpox exposure as protection against smallpox | Proof the idea was in the air before Edward Jenner acted on it |

| Jenner’s developing plan | Use cowpox intentionally, then watch for protection over time | Sets up the move from rumor to repeatable medical method |

The First Vaccination

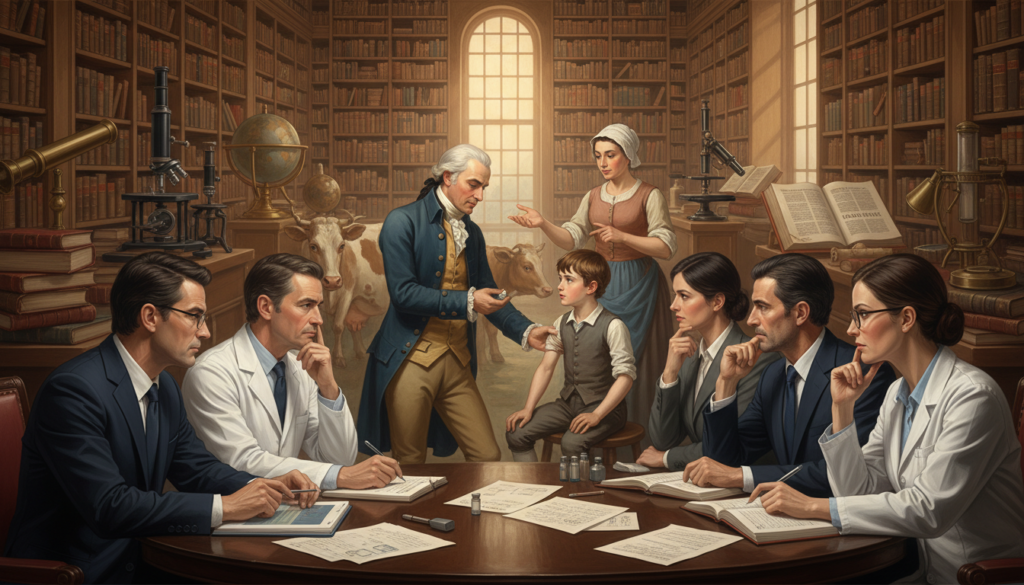

Imagine a quiet English village in 1796. Fear of smallpox was always there. Edward Jenner didn’t have fancy tools. He had notes, stories, and a big idea about cowpox.

In May 1796, Jenner’s idea became a real, risky moment. A dairymaid named Sarah Nelms had cowpox sores. Jenner saw a chance and acted fast.

Methodology of Jenner’s Approach

On May 14, 1796, Jenner took material from Sarah Nelms’s cowpox sores. He then gave it to an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps. It was a hands-on approach, based on careful observation.

This method was surprisingly simple. No fancy tools were needed. It was a controlled way to try to protect against smallpox, without the dangers of variolation.

- Date: May 14, 1796

- Source: cowpox lesions on Sarah Nelms

- Recipient: James Phipps, age 8

- Goal: build protection without triggering full smallpox disease

Results of Initial Trials

After the cowpox inoculation, James Phipps had a local reaction. He felt unwell for several days. He had mild fever and discomfort in the armpits.

About nine days later, he felt chilled and lost his appetite. But he felt better the next day.

Then, in July 1796, Jenner tested Phipps again. This time, he used material from a fresh human smallpox lesion. This was to see if the earlier vaccination had worked.

Jenner also gave the idea a name. “Vaccine” comes from the Latin word for cow, vacca. This helped people understand it as something new and different from old smallpox practices.

| Detail | Cowpox Inoculation (Jenner’s method) | Variolation (older practice) |

|---|---|---|

| What was used | Material from cowpox sores (like Sarah Nelms’s lesions) | Material from a human smallpox lesion |

| Typical intensity | Often milder symptoms, with a localized reaction and short illness | Could cause a full smallpox case, sometimes severe |

| Main risk | Uncertainty about protection and how strongly a person would react | Higher chance of dangerous illness and wider spread to others |

| Why it drew attention | Edward Jenner wrote detailed observations that made the approach easier to judge | Known approach, but feared because outcomes could be unpredictable and deadly |

Public Reception of Vaccination

New ideas in medicine don’t always get a warm welcome. The story of smallpox vaccination is a good example. Even with strong results, it faced many challenges.

Edward Jenner’s discovery quickly became a topic of debate. This shows how fast a new idea can spark controversy.

In 1797, Jenner sent his work to the Royal Society, but it was rejected. So, in 1798, he published his own booklet, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae… Known by the Name of Cow Pox. It was a mix of case report and debate, standing at the crossroads of old and new.

Skepticism and Resistance

Many people were hesitant, for good reasons. Some worried about side effects. Others were uneasy about using animal products. And many stuck with variolation, even with its risks.

Jenner’s booklet gave critics plenty to argue with. He claimed cowpox started in horses and spread to cows, a claim that didn’t hold up. Plus, finding volunteers in London was tough, which made things harder.

Support from the Medical Community

But then, things started to change. Other doctors began to support Jenner. Surgeon Henry Cline helped spread the idea in London. In 1799, Dr. George Pearson and William Woodville also supported vaccination, adding more voices to the conversation.

Jenner conducted a wide survey. He asked for reports of people who didn’t catch smallpox after getting cowpox. These stories helped build trust in the new method.

Despite this, early vaccination efforts faced challenges. Supplies were limited, and quality varied. Jenner shared his material with many, helping the idea spread through personal connections. This grassroots approach played a big role in gaining acceptance.

| What people questioned | What fueled the worry | What helped shift attitudes |

|---|---|---|

| Safety compared with variolation | Smallpox inoculation was familiar, even with known danger | More reports of protection after cowpox exposure |

| Credibility of Edward Jenner’s claims | Royal Society rejection and arguments over his early theory | Independent use by Henry Cline, George Pearson, and William Woodville |

| Trust in the material itself | Confusion about sourcing, handling, and consistency | Person-to-person sharing networks that made access more practical |

| Social and cultural discomfort | Animal-origin talk and rumors spreading faster than evidence | Everyday observations from communities watching outcomes over time |

Advancements in Vaccination

Jenner’s first shot didn’t just fight smallpox. It started a chain reaction that shapes your doctor’s office today. He’s seen as the father of immunology, even though others noticed cowpox protection before him. His method, notes, and the spread of his work made the difference.

His “write it down and prove it” mindset is why he’s called a pioneering immunologist. Not for working in a modern lab (he didn’t). But for turning a local idea into a public health tool.

From Jenner to Modern Vaccines

After Jenner, things moved fast. Louis Pasteur started lab work in the 1870s, even with a stroke and personal loss. In 1885, he used post-exposure rabies vaccination on Joseph Meister—13 injections that got stronger.

Meister survived and later cared for Pasteur’s tomb in Paris.

By the late 1800s, work got more specialized. In 1894, Dr. Anna Wessels Williams isolated a diphtheria strain key for antitoxin development. It marked a shift from folklore to microbiology and standardization.

Case Studies of Successful Vaccines

The 1900s saw big wins. In 1937, Max Theiler, Hugh Smith, and Eugen Haagen developed the 17D yellow fever vaccine. It was approved in 1938, and over a million people got vaccinated that year. Theiler later won a Nobel Prize for this breakthrough.

Then, pertussis vaccines showed strong results. In 1939, Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering’s vaccine cut child sickness rates from 15.1 to 2.3 per 100. Influenza vaccine approvals followed soon, thanks to Thomas Francis Jr. and Jonas Salk’s research.

Polio became a focus in the mid-century. Jonas Salk developed the first effective polio vaccine from 1952 to 1955. He tested it on himself and his family, and field trials involved over 1.3 million children. By 1960, Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine was approved, leading to polio elimination in Czechoslovakia.

Throughout vaccination history, we see a pattern: careful observation, better tools, larger trials, and wider access. Jenner’s work started this pattern. And the pioneering immunologist mindset remains important today.

| Milestone | People | Year(s) | What happened | Why it mattered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-era vaccine work begins | Louis Pasteur | 1872 | Creates a laboratory-produced vaccine for fowl cholera in chickens | Moves vaccination history from field observation toward controlled lab methods |

| Post-exposure rabies vaccination | Louis Pasteur; Joseph Meister | 1885 | Meister receives 13 injections with increasingly stronger doses and survives | Shows vaccines can work even after exposure, changing emergency care thinking |

| Diphtheria strain isolation | Dr. Anna Wessels Williams | 1894 | Isolates a diphtheria strain key for antitoxin development | Supports safer, more reliable production tied to specific microbial strains |

| Yellow fever 17D vaccine | Max Theiler; Hugh Smith; Eugen Haagen | 1937–1938 | 17D vaccine developed, approved in 1938, with over a million vaccinated that year | Creates a durable prevention tool and becomes a landmark success in modern immunology |

| Pertussis vaccine efficacy demonstrated | Pearl Kendrick; Grace Eldering | 1939 | Child sickness rates drop from 15.1 per 100 children to 2.3 per 100 | Delivers clear population-level impact that helps win public trust |

| Influenza vaccine approvals | Thomas Francis Jr.; Jonas Salk | 1945–1946 | Approved for military use in 1945 and civilians in 1946 | Shows fast adaptation to shifting strains and large-scale deployment needs |

| Polio vaccines scale up | Jonas Salk; Albert Sabin | 1952–1960 | Salk vaccine developed and mass-tested in 1954 with over 1.3 million children; Sabin oral vaccine approved by 1960 | Turns polio from a feared seasonal threat into a target for elimination programs |

Global Impact of Vaccination

When you look at the big picture, it’s not just about one doctor in England. Edward Jenner’s work in 1796 started a global effort. People could share and grow his idea of smallpox vaccination, using just notes and trust.

By 1800, smallpox vaccination spread quickly in England and Europe. By 1803, Jenner’s findings were translated into French and Spanish. This made it easier to share across borders and through different systems.

Reduction of Smallpox Incidence

The early success wasn’t magic. It was from doing it over and over. Jenner sent vaccine to friends and anyone who asked. They shared it, creating a chain of help.

In 1800, Dr. John Haygarth got vaccine from Jenner. He sent it to Benjamin Waterhouse at Harvard. This helped start smallpox vaccination in the United States.

Over time, these small wins added up. By the mid-1900s, smallpox was almost gone in Western Europe, North America, and Japan. This was thanks to constant vaccination and better health rules.

Vaccination Policies Worldwide

Governments didn’t just watch; they helped push it forward. Napoleon Bonaparte and Thomas Jefferson supported Jenner’s work. This gave the vaccine more credibility when people were skeptical.

Spain took a big step too. After Jenner’s work was shared in Spanish, the King of Spain started a vaccination campaign. This campaign reached the Americas and the Far East, using government planning.

In 1967, the World Health Organization launched a big program to stop smallpox. They aimed to end it in over 30 countries using surveillance and vaccination. Eradication meant no more risk of it coming back.

Even during the Cold War, public health efforts kept going. The United States and the Soviet Union worked together on this. It showed how important stopping smallpox was, no matter the politics.

| Milestone | What happened | Why it changed reach |

|---|---|---|

| 1796 | Edward Jenner tests the vaccine idea using cowpox | Creates a repeatable method people can teach and copy |

| 1800 | Jenner shares vaccine material; John Haygarth sends it to Benjamin Waterhouse at Harvard | Builds person-to-person distribution networks across the Atlantic |

| 1803 | Jenner’s findings appear in French and Spanish | Makes smallpox vaccination easier to adopt in more governments and clinics |

| 1803 | Spain launches a vaccination campaign to the Americas and the Far East | Turns vaccination into organized, large-scale public action |

| 1967 | WHO begins the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme | Pairs surveillance with vaccination to stop transmission country by country |

| 1980 | World Health Assembly declares smallpox eradication | Marks the first time a human disease is officially removed from nature |

Ethical Considerations

Looking back at vaccination history, we see both good and bad. Progress was fast, but it was also scary. Infectious diseases were spreading quickly, forcing tough choices.

Early methods were sometimes harsh. Variolation, for example, used smallpox to try to prevent a worse illness. It worked sometimes, but it could also spread disease.

Informed Consent in Vaccination

Today, we expect clear choices in health care. We learn about risks and benefits before deciding. But, this wasn’t always the case, when fear was high.

Variolation raised big questions about consent. In 1721, Charles Maitland tested it on prisoners who hoped for freedom. Later, orphaned children were also used. The Royal Society and College of Physicians watched, but power was a big issue.

There were real risks. Some got full smallpox and could spread it. People worried about other infections too. Even if variolation worked, it killed 2%–3% of those who got it.

| Ethics Question You’d Ask | How Variolation Often Looked | What Modern Consent Tries to Require |

|---|---|---|

| Was the choice truly voluntary? | Prisoners and orphans faced pressure, rewards, or limited options | Freedom to refuse without punishment or loss of care |

| Were risks explained in plain language? | Benefits were emphasized; dangers and spread risk weren’t always clear | Clear, simple risk talk and time for questions |

| Could it harm other people? | Recipients could transmit smallpox during illness | Safety plans to reduce community exposure and monitor outcomes |

| Was there oversight beyond prestige? | Elite observation existed, but rules were loose and inconsistent | Independent review, written protocols, and ongoing safety checks |

The Role of Ethics in Medical Innovation

Innovation moves fast when diseases are pressing. This urgency can push for quick fixes. But, it’s important to keep careful checks.

Today, we aim for speed and safety. We want clear information, strong monitoring, and real consent. We also acknowledge that some old practices, like variolation, wouldn’t pass today’s ethics.

Vaccination and Herd Immunity

Herd immunity is simple: enough people protected means fewer places for germs to spread. This is how communities fight off diseases, even before we knew about viruses. It’s why eradicating smallpox worked when everyone helped, not just some.

History shows us how it works. When doctors in Europe supported variolation, it spread faster. Leaders like King Frederick II of Prussia and George Washington used it in their armies. It wasn’t perfect, but it showed how a plan can help stop outbreaks.

Understanding Herd Immunity

Think of an outbreak like a string of matches. If many are “damp” from vaccination, the spark fizzles out. You don’t need everyone protected, but enough to slow down the spread.

But “enough” varies by disease. Some spread so easily that a small gap can keep it alive. So, herd immunity is not a magic shield. It’s a goal that changes based on how contagious the germ is and how many are protected.

| Real-world piece of the puzzle | What it looks like in practice | Why it matters for herd immunity |

|---|---|---|

| High coverage | Most people get vaccinated on schedule, and boosters are common | Transmission chains break more often, so outbreaks struggle to grow |

| Coverage gaps | Neighborhoods or age groups skip shots, delay them, or miss boosters | Pockets of spread stay open, letting infectious diseases rebound |

| Organized delivery | Clinics, schools, employers, and military systems help coordinate access | Protection becomes predictable and widespread, not random or uneven |

| Clear rules and trust | Steady expectations shaped by vaccination policies worldwide, plus simple messaging | More people follow through, which keeps community protection stable |

Importance of Community Vaccination

Community vaccination is key to big wins. Eradicating smallpox didn’t happen because one person avoided it. It happened because whole regions worked together to increase coverage.

When diseases are rare, it’s easy to get complacent. In the United States, whooping cough hit a low in 1976. But some started worrying more about rare side effects than the disease itself. This can create gaps where outbreaks can start again.

We also saw global thinking. The World Health Organization started the Expanded Programme on Immunization in 1974. It aimed to strengthen vaccination programs worldwide against diseases like diphtheria, measles, and polio. It’s like a global effort to keep diseases from spreading easily.

Misconceptions About Vaccination

Looking into vaccination history, we see doubt has always been around. It’s loud, emotional, and sometimes weirdly creative.

Myths grow when fear beats facts. They grow when change happens too fast for us to keep up.

Common Myths Dispelled

Before Edward Jenner, doctors debated variolation. Reports from Istanbul didn’t change minds in England right away. Emanuel Timoni wrote to the Royal Society in 1714, and Giacomo Pilarino followed in 1716.

In Boston’s 1721 crisis, things got intense. Cotton Mather pushed variolation. He convinced Zabdiel Boylston to try it, but faced backlash. Someone even threw a bomb into Mather’s house.

What mattered wasn’t a slogan. It was numbers. Mather and Boylston showed variolation had a 2% fatality rate. This was compared to 14% for natural smallpox in an outbreak that hit half of Boston’s 12,000 residents.

Edward Jenner faced criticism that had nothing to do with his vaccine. Critics questioned his cuckoo research, saying he was careless. But photography later proved his observations in 1921.

| Claim you’ll hear | What happened historically | What helped people judge it |

|---|---|---|

| “Doctors are hiding bad outcomes.” | During Boston’s 1721 epidemic, Cotton Mather and Zabdiel Boylston tracked results and published comparisons. | Simple outcome counts, shared in public, made the debate less about rumor. |

| “New methods are unnatural and dangerous.” | Early English physicians resisted variolation even after reports by Emanuel Timoni (1714) and Giacomo Pilarino (1716). | Repeated observation over time, plus clearer explanations of risk, slowly moved opinions. |

| “If one detail is questioned, the whole idea fails.” | Critics attacked Edward Jenner by pointing to alleged flaws in his cuckoo work, not just his smallpox vaccination efforts. | Independent confirmation (including later photography) showed why one dispute doesn’t erase a broader body of evidence. |

Educating the Public

To sort fact from myth, start with simple language. Ask about the disease risk, the procedure risk, and what real comparisons show.

Vaccination history shows calm explanation works better than shouting. Real numbers give us something solid to hold onto, even when the story around a vaccine gets loud.

Continuing Jenner’s Legacy

Jenner’s idea of using cowpox to block smallpox is seen in today’s vaccines. These vaccines move quickly from labs to clinics. They also share data across borders.

Big efforts didn’t just happen. They were built step by step. Vaccination policies worldwide turned local wins into global routines. Today’s vaccines are about more than just a formula in a vial. They involve cold-chain logistics, training, trust, and timing.

Modern Vaccination Efforts

Take polio. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative started in 1988. By 1994, polio was gone from the Americas. Europe followed in 2002, and by 2003, it was in just six countries.

Now, let’s look at how vaccines get updated. The first rotavirus vaccine was approved in 1999. It was pulled about a year later because of safety concerns. A safer version came in 2006 and is now used in over 100 countries.

Some breakthroughs take a long time. After finding the hepatitis B virus, a vaccine was developed by 1969. A plasma-derived vaccine was used from 1981 to 1990. A recombinant vaccine from 1986 is also used today.

HPV prevention followed a similar path. Research helped link HPV to cervical cancer. The first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006. In Africa’s meningitis belt, a vaccine project nearly eliminated a disease in five years.

The Future of Vaccination Research

Outbreaks push for speed, but speed needs a plan. WHO’s R&D Blueprint helps research and development during epidemics. This includes trials and manufacturing.

New targets keep coming. The RTS/S malaria vaccine pilot started in 2019. It tested delivery in real clinics. A new smallpox vaccine was approved for monkeypox, marking the first monkeypox vaccine.

COVID-19 changed our timeline. WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020. The first vaccine doses were given in December 2020. But, inequity was a big issue, with most doses going to a few countries.

| Milestone | Key dates | What it shows you |

|---|---|---|

| Global Polio Eradication Initiative | 1988 launch; 1994 Americas; 2002 Europe; 2003 endemic in six countries | Coordination at scale can shrink a virus’s footprint fast when strategy and funding stay steady. |

| Rotavirus vaccine revision | 1999 approval; ~2000 withdrawal; 2006 lower-risk version; 2019 used in 100+ countries | Safety monitoring can reshape modern vaccines without ending the mission. |

| Hepatitis B vaccine progress | 1969 heat-treated approach; 1981–1990 plasma-derived commercial use; 1986 recombinant vaccine | Big prevention wins can take decades, with science and manufacturing improving in layers. |

| HPV vaccine | 2006 first approval | Linking screening research to prevention can change lifetime cancer risk at the population level. |

| Ebola vaccine readiness | WHO prequalification; 2021 global stockpile | Preparedness matters when outbreaks flare in hard-to-reach places. |

| COVID-19 vaccine rollout | Jan 30, 2020 PHEIC; Mar 11, 2020 pandemic; Dec 2020 first doses; July 2021 access gaps | Speed is possible, but fairness depends on supply, pricing, and vaccination policies worldwide. |

Conclusion: The Importance of Vaccination

Look how far we’ve come. What started as a risky idea in the 1700s has changed life everywhere. Vaccines have saved more lives than any other medical tool.

Edward Jenner’s test with cowpox in 1796 was bold. He wrote down every detail. This helped others see vaccination was safer than variolation.

Reflections on Edward Jenner’s Influence

Smallpox was once a huge problem. Reports showed scars, blindness, and death everywhere. But in 1980, smallpox was eradicated.

This was a huge victory. It happened because communities kept showing up, even when it was hard.

Call to Action for Vaccination Awareness

Vaccine doubts aren’t new. Edward Jenner faced pushback, and so did later efforts. Stay curious and check solid sources like the CDC.

Ask questions and remember: community protection depends on participation. We’re exploring new diseases and tools. Your choices help decide what risks future generations won’t face.

FAQ

Why does Edward Jenner’s smallpox story matter today?

Why is smallpox discussed as a risk after September 11, 2001?

Who was Edward Jenner, beyond the “father of immunology” label?

How did Jenner train as a doctor and scientist?

What did Jenner do beside smallpox vaccination?

What was medicine like in Jenner’s time—did people understand germs?

Where did smallpox come from, and how far back does it go?

How did smallpox become a global disaster?

Was smallpox ever used as a weapon?

How deadly was smallpox in real numbers?

Why was it called “variola,” and where did “smallpox” get its name?

What is variolation, and why did people do it before vaccination?

How did the cowpox clue enter the story?

Was Jenner the first person to think cowpox could prevent smallpox?

What happened in the famous 1796 vaccination experiment?

How did Jenner test whether the cowpox inoculation worked?

Why was vaccination safer than variolation?

Where do the words “vaccine” and “vaccination” come from?

Did the Royal Society accept Jenner’s findings right away?

What did Jenner’s 1798 “Inquiry” actually argue?

How did vaccination spread if people were skeptical?

Why is Edward Jenner considered a pioneering immunologist and “father of immunology”?

What were major vaccine milestones after Jenner?

What are a few modern vaccination milestones that echo Jenner’s legacy?

How did vaccine science respond to major outbreaks in recent years?

What did COVID-19 change about how people think about vaccines?

Why do orthopox viruses, like monkeypox, matter if smallpox is eradicated?

Get More Medical History

Join our newsletter for fascinating stories from medical history delivered to your inbox weekly.

The History of Healing

The History of Healing