The White Plague: History and Its Secrets

Explore the white plague, a historical disease that continues to intrigue us. Uncover its history, impact, and the surprising facts surrounding it.

What if we told you a single germ might have killed more people than any other in all of known human history? It’s a staggering thought, right? This wasn’t a war or a natural disaster. It was a disease.

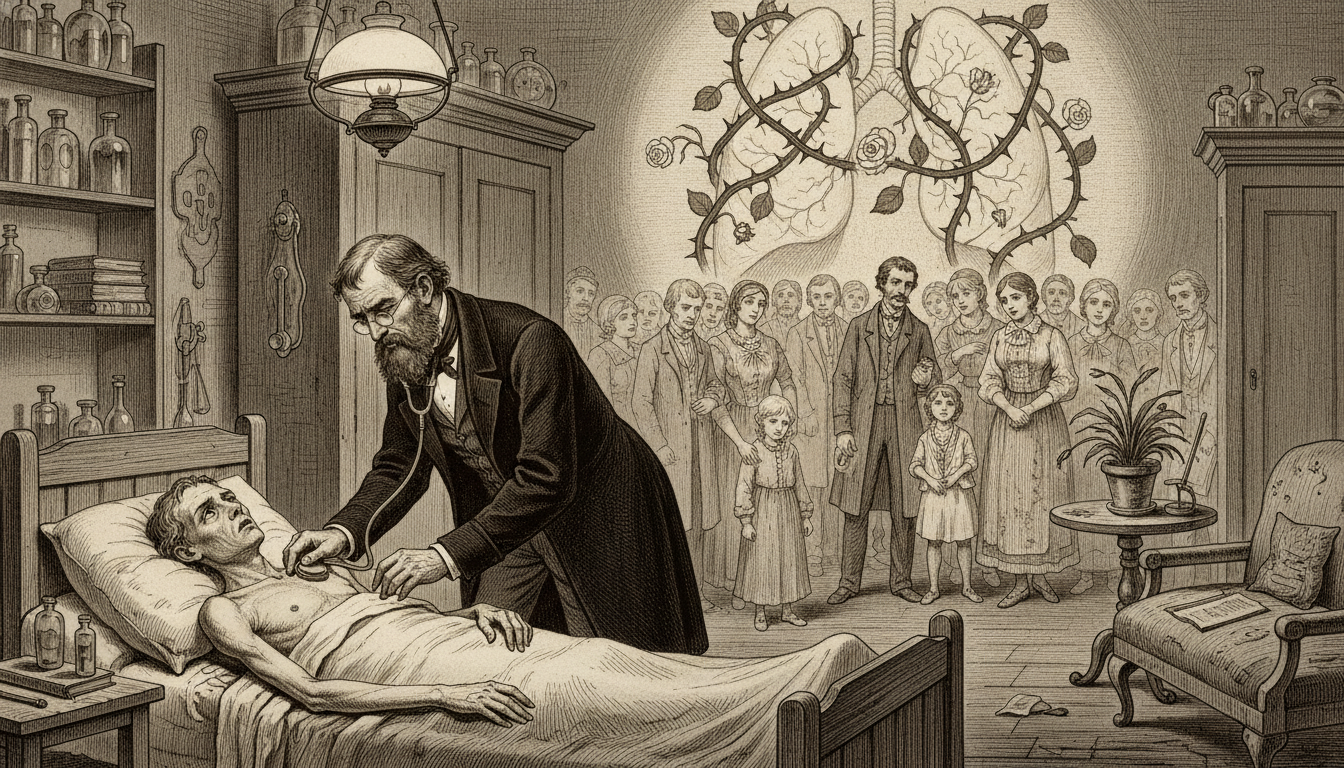

You’ve probably heard its old, poetic names whispered in history books: consumption, the robber of youth. In 1861, physician Oliver Wendell Holmes called it the white plague. But this was no fairy tale. This killer was tuberculosis.

This illness didn’t just make people sick. It shaped our entire world. It influenced art, changed cities, and haunted generations. Understanding this chapter of history isn’t just about the past. It shows us how far we’ve come in fighting tuberculosis today.

Key Takeaways

- Tuberculosis is potentially the deadliest infectious disease in human history.

- It has been known by many names, including “consumption” and “the white plague.”

- The disease had a massive impact on art, literature, and public health policies.

- Learning its history helps us appreciate modern medical advancements.

- Its story connects ancient civilizations to relatively recent times.

Introduction to Tuberculosis and Its Enduring Impact

Have you ever wondered what connects Egyptian mummies to modern medical challenges? The answer lies in a persistent bacterial infection that has traveled through time with us.

Defining the White Plague

So what exactly is tuberculosis? It’s caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a sneaky bacterium that primarily targets your lungs. But here’s the surprising part—it can infect almost any organ in your body.

The bacteria travel through the air when someone coughs or sneezes. This makes lung infections most common, but the disease can spread to bones, brain, or kidneys.

| Aspect | Ancient Evidence | Modern Reality |

|---|---|---|

| First Appearance | 8000 BCE remains | Still active today |

| Geographic Spread | Egyptian mummies (2400 BCE) | Global infection |

| Annual Impact | Historical records | 2 million deaths yearly |

| Primary Target | Bone evidence | Lung infections |

Historical Significance and Modern Relevance

You might think tuberculosis is ancient history. But here’s the reality check: over two million people still die from this disease every year worldwide.

Understanding TB’s journey helps us appreciate why it shaped medical history and public health policies. As one historian noted,

This infection changed how we think about contagion and isolation—concepts we still use today.

The battle against this bacterial enemy continues across our modern world. Its story reminds us that some medical challenges truly stand the test of time.

Origins and Early Descriptions of Tuberculosis

Long before microscopes or modern medicine, ancient doctors were already wrestling with a disease we now call tuberculosis. They didn’t have our modern term, but they certainly recognized its devastating pattern.

Ancient Records and Mythologies

Way back in the second millennium BCE, King Hammurabi’s legal code mentioned a chronic lung condition. Historians now believe this was probably tuberculosis.

The ancient Chinese medical text Huang Ti Nei-Ching described a “wasting disease” around the same time. Even Homer’s Odyssey from the 8th century BCE talks about “grievous consumption” stealing souls from bodies.

Descriptions by Hippocrates and Aretaeus

Hippocrates, around 400 BCE, called it “phthisis” – Greek for “to waste away.” He noted it was the most common disease of his century and usually fatal.

Here’s something remarkable: Hippocrates observed that phthisis mainly attacked people between 18 and 35 years old. The disease truly was a robber of youth.

Aretaeus of Cappadocia later described the coughing up of blood that characterized advanced tuberculosis. Claudius Galen actually found tubercles in diseased lungs and warned the illness was contagious.

| Ancient Source | Time Period | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Hammurabi’s Code | 2nd millennium BCE | Chronic lung condition |

| Chinese Nei-Ching | 3rd millennium BCE | “Wasting disease” |

| Hippocrates | 400 BCE | Common fatal disease in youth |

| Aretaeus | 2nd century CE | Coughing blood symptoms |

Medical Insights from Antiquity to the Renaissance

Before modern medicine gave us antibiotics, physicians had to get creative—sometimes wildly creative—in their battle against tuberculosis. They threw everything at the wall to see what might stick.

The Role of Early Physicians and Traditional Remedies

Hippocrates had a surprisingly sensible approach. He recommended good food, plenty of milk (especially from donkeys), and exercise. At least these wouldn’t hurt patients!

Then came Galen, who really upped the bizarre factor. He prescribed fresh air, human breast milk, wolf livers, and even elephant urine. Wealthy patients got sea voyages to warm climates like Egypt.

Bloodletting was the go-to treatment for almost everything. Aretaeus suggested spiritual healing in cypress groves. Some ideas were pleasant, if not effective.

| Physician | Time Period | Recommended Treatment | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocrates | 400 BCE | Good food, donkey milk, exercise | Strengthen the body |

| Galen | 2nd century CE | Wolf livers, elephant urine, sea voyages | Balance humors, change environment |

| Aretaeus | 2nd century CE | Cypress grove stays | Spiritual and fresh air therapy |

| Common Practice | Medieval Era | Bloodletting | Balance bodily fluids |

By 1679, Sylvius de la Boë gave us the term “tubercles” for the nodules in lungs. Richard Morton later suggested the disease might spread through close contact. This way of thinking would eventually work, but not for another two centuries.

Evolution of Tuberculosis Treatments and Public Health Measures

What if your doctor prescribed burning your own spit as a health measure? That’s exactly what public health officials recommended in the early 1900s when fighting tuberculosis. They were desperate to stop this killer disease.

By 1906, the Iowa State Board of Health had some wild ideas. They told people to boil handkerchiefs for half an hour. They said to shave off beards and mustaches. Patients had to spit in special cups and burn them.

Sanatoriums and the Fresh Air Cure in America

The fresh air obsession became huge. Doctors called patients “lungers” and sent them to mountain states. They believed clean air could heal.

Imagine sleeping outside on a porch with snow drifting onto your blankets! That was real treatment. Patients spent months isolated from family. They just rested and breathed fresh air.

Iowa built the Oakdale sanatorium in 1907. This massive facility housed over 500 patients by 1910. They ate nutritious food and stayed outdoors constantly.

The Shift from Traditional Practices to Modern Medicine

These extreme measures actually worked. Iowa’s tuberculosis death rates dropped dramatically. They went from 2,000 deaths in 1906 to just 600 by 1934.

By the mid-1940s, Iowa had the lowest TB death rate in the country. This proved public health measures could make a difference. Good nutrition, rest, and isolation helped many patients recover.

The battle against this disease was long and difficult. But these early efforts paved the way for modern treatments we have today.

White Plague: A Historical Perspective on Tuberculosis

What’s in a name? For tuberculosis, the answer is centuries of fear and misunderstanding. The labels people gave this disease reveal how they saw it—and how little they understood it.

Coining of the Term and the White Death

For generations, regular people called it “consumption.” The name fit perfectly. Patients literally appeared to be consumed from within, wasting away before everyone’s eyes.

Doctors preferred the Greek term “phthisis.” It sounded more scientific but meant the same thing—wasting away. Both names were used until the mid-19th century.

Then came a breakthrough. In the 1830s, Johann Lukas Schönlein noticed the tubercles in infected lungs. He combined this observation with the Greek word for swelling to create “tuberculosis.” Finally, the disease had a medically accurate name.

But the most dramatic name emerged during the devastating 19th century epidemic. Oliver Wendell Holmes called it the “white plague” in 1861. He wanted to compare its death toll to history’s worst plagues.

The “white” described patients’ ghostly pale complexion from severe anemia. Some historians think it also referenced the disease’s tragic preference for young victims. The name captured both medical reality and social tragedy in one powerful term.

Each name change marked a shift in how people understood this killer over time. From fearful descriptions to scientific labels, the evolution of tuberculosis terminology tells its own fascinating story.

Impact on Society, Culture, and the Arts

Can you imagine a disease so deadly that society started calling it beautiful? That’s exactly what happened with tuberculosis during the 19th century. While millions of people died horrible deaths, a strange cultural phenomenon emerged.

The Romanticization of Consumption

Here’s where history gets really strange. Between 1851 and 1910, four million people died from this disease in England and Wales alone. Yet somehow, society transformed this horror into something romantic.

The illness created a specific “look” that became desirable. Patients appeared thin, pale, and melancholy. This “wan and pallid” appearance was considered attractive, especially in women. It was called a “terrible beauty.”

| Romanticized Ideal | Medical Reality | Cultural Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Pale, delicate appearance | Severe anemia and weakness | Fashionable beauty standard |

| “Ethereal” quality | Chronic coughing and fatigue | Artistic inspiration |

| Tragic youthfulness | High death rate among young adults | Literary theme |

| Slow, “beautiful” death | Painful, prolonged suffering | Social acceptance |

Literary and Artistic Representations

Writers and poets absolutely embraced this imagery. Lord Byron famously said he wanted to die of consumption because it would make him look “interesting.” John Keats, who died from tuberculosis at just 26 years, wrote about how “youth grows pale, and spectre thin, and dies.”

Edgar Allan Poe described his dying wife as “delicately, morbidly angelic.” The entire Brontë family was devastated by the disease, yet Emily still wrote romantic descriptions in Wuthering Heights. This morbid fascination shaped artistic work for generations.

This romanticization only happened because the disease primarily affected young, creative people who had the time to die slowly. It was a strange way for society to cope with overwhelming death.

Breakthroughs in Medical Science and Tuberculosis Research

Sometimes the simplest inventions change medicine forever—like a rolled-up notebook. That’s exactly what French doctor René Laennec used in 1816 when he created the first stethoscope. He called his method “mediate auscultation,” giving doctors their first real tool to listen inside the chest.

Laennec’s wooden tube wasn’t just about sound. It let him connect what he heard in living patients with what he found during autopsies. He described how tiny “miliary” tubercles formed in the lung, growing into cheese-like material that broke down into cavities.

Robert Koch’s Discovery and Its Significance

The absolute game-changer came in 1882 when Robert Koch identified the tuberculosis bacillus under his microscope. This discovery was monumental—it finally proved that scrofula, lung infections, and all other forms were the same disease.

Robert Koch‘s work settled decades of debate about the cause of this devastating infection. For the first time, doctors could definitively diagnose tuberculosis by identifying the specific bacteria.

Advancements in Diagnostic Techniques

Laennec essentially invented the vocabulary of chest medicine. Terms like “auscultation” and “râle” came from his work. Tragically, he died from the very disease he studied in 1826.

Robert Koch‘s identification of the bacilli laid the foundation for modern medicine. His discovery in the 19th century paved the way for everything that followed—vaccines, antibiotics, and eventually controlling a disease that plagued humanity for millennia.

Personal Narratives and Societal Perceptions

What if your childhood home had separate silverware, separate bedrooms, and a live-in nurse—all because of one illness? This was the reality for many families dealing with tuberculosis in early 20th century America.

Firsthand Accounts and Family Histories

One powerful memoir describes growing up with a mother who spent seven years at Saranac Lake sanitarium in upstate New York. She returned home “improved but far from cured” in the late 1920s.

The family lived in constant vigilance. The mother had her own wing with separate bedroom, bath, and sleeping porch. A trained nurse lived with them full-time. Children were told to scrub hands before eating and keep their distance.

Every cough was measured for danger. The mother coughed into cardboard boxes that were immediately burned. Sputum samples went regularly to Dr. Lawrason Brown at Saranac for analysis.

| Public Perception | Medical Reality | Impact on Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Highly contagious like leprosy | Required prolonged direct exposure | Complete social isolation |

| Fear-driven avoidance | Controlled through proper hygiene | Families were shunned |

| Moved out of communities | Sanitarium treatment effective | Separate living arrangements |

| Moral judgment | Bacterial infection | Psychological trauma |

Dr. Brown’s book, Rules for Recovery From Pulmonary Tuberculosis, emphasized rest above all. “Never stand when you can sit. Never sit when you can lie,” he advised. Patients consumed huge quantities of milk as part of their treatment.

Edward Livingston Trudeau’s own recovery story inspired the Saranac mountain community. He arrived in 1875 so wasted that a helper remarked he weighed “no more than a dried lambskin.” His miraculous recovery led to founding the famous sanitarium.

Wealthy patients stayed at the elegant Santanoni hotel with its specialized sleeping porches. Famous guests included Philippine President Manuel Quezon and baseball star Christy Mathewson. Snow would drift onto blankets as patients slept outdoors—part of the fresh-air cure.

Conclusion

You might be surprised to learn that the battle against tuberculosis isn’t actually over—it just looks different today. The real game-changer came in 1944 with the discovery of streptomycin, the first antibiotic that could kill the TB bacteria.

What once meant certain death now means a year of drugs like isoniazid and rifampin. Most people continue their normal lives during treatment. The numbers tell an amazing story: TB deaths dropped from 88,000 Americans in 1930 to just 3,513 by 1974.

But here’s the reality check. While wealthy countries have nearly eliminated this disease, it still kills over two million people yearly worldwide. Even Iowa sees 40-60 new cases each year.

Drug-resistant strains remind us that bacteria evolve. The history of the white plague teaches us that diseases shape civilizations and drive medical innovation. Understanding this history helps us fight the health battles of today and tomorrow.

FAQ

What exactly was the "White Plague"?

How did doctors treat patients before modern drugs?

Why was tuberculosis sometimes romanticized?

What was Robert Koch’s huge breakthrough?

Is tuberculosis still a problem today?

Get More Medical History

Join our newsletter for fascinating stories from medical history delivered to your inbox weekly.

The History of Healing

The History of Healing