William Harvey’s Discovery of Blood Circulation

Explore the landmark breakthrough by William Harvey unveiling the circulation of blood, reshaping our understanding of the cardiovascular system.

Your heart pumps about 2,000 gallons of blood daily. This fact makes an old idea seem crazy. For centuries, doctors thought blood was “used up” and replaced.

In early 1600s London, William Harvey asked tough questions. Why do veins have one-way valves? How can the heart keep up with constant new blood?

Between 1617 and 1628, Harvey’s discovery took shape. He watched beating hearts, studied vein valves, and did math. His work was surprisingly direct.

By 1628, when he published *De Motu Cordis* in Frankfurt, his argument was clear. The circulation of blood runs in a loop. This changed how doctors treated patients, making bloodletting seem less logical.

Once you see how William Harvey built his case, you’ll wonder how medicine missed it.

Key Takeaways

- William Harvey showed that the circulation of blood moves in a continuous loop through the cardiovascular system.

- Harvey’s discovery grew over roughly a decade of work (about 1617–1628), mostly tied to his life and practice in London.

- In 1628, he published *De Motu Cordis* in Frankfurt, laying out his evidence in plain, testable steps.

- He challenged Galen’s long-held model that blood was constantly made and used up.

- Vein valves, live-animal observation, and simple math were key tools in proving his point.

- Once circulation of blood was accepted, old treatments like bloodletting looked far less logical.

Introduction to William Harvey’s Life and Contributions

Before he became famous for his ideas on circulation, William Harvey was a real person. He lived in busy places, went to loud schools, and worked in cramped rooms. As a 17th-century scientist, he didn’t just think about ideas. He looked for proof, step by step, through his medical research.

His journey makes his later breakthroughs seem less magical and more like a natural flow. Travel, training, and daily work at the hospital pushed him to keep asking questions.

Early Life and Education

William Harvey was born on April 1, 1578, in Folkestone, Kent, England. He learned Latin early and then went to The King’s School, Canterbury, for five years. This training helped him read closely and argue well, skills he used in his research.

In 1593, he started at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and got his B.A. in 1597. He then traveled to France and Germany, and later to Italy. By 1599, he was at the University of Padua, where he studied intensely and asked sharp questions.

Career Beginnings

At Padua, William Harvey got his M.D. in 1602, at age 24. He then returned to England and joined the Royal College of Physicians on October 5, 1604. A few weeks later, he married Elizabeth Browne, and they had no children.

He quickly became well-respected. He became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP) on June 5, 1607. In 1609, he took a big role at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, becoming the top doctor on October 14, 1609.

This job had strict rules. He had to treat poor patients honestly, without gifts or favors. For a 17th-century scientist, this wasn’t just a rule—it was a way of life.

In 1615, he became the Lumleian Lecturer at the College of Physicians (August 4, 1615). His lectures started in April 1616. Teaching anatomy in public helped him build trust and test his ideas through research.

Key Influences

At Padua, William Harvey studied under Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente. Fabricius’s work on venous valves helped Harvey think differently about blood movement. Fabricius published De Venarum Ostiolis in 1603, and Harvey deeply absorbed and built upon it.

Then, he got a big chance at the royal court. He was appointed Physician Extraordinary to King James I on February 3, 1618, and later to King Charles I. Working at court gave him access to animals for study, helping him in his research.

| Year | Where Harvey Was | What Was Happening | Why It Mattered for Medical Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1578 | Folkestone, Kent | Birth of William Harvey (April 1) | Roots in a port town that connected him early to travel and wider ideas |

| 1593–1597 | Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge | Matriculated (1593), earned B.A. (1597) | Built the reading, logic, and debate skills that supported later experiments |

| 1599–1602 | University of Padua | Entered Padua (1599), earned M.D. (dated April 25, 1602) | Training under a practical culture of anatomy pushed him toward evidence over tradition |

| 1604–1607 | London | Admitted to Royal College of Physicians (Oct 5, 1604); became FRCP (June 5, 1607) | Professional status gave his work an audience and steady clinical exposure |

| 1609 | St. Bartholomew’s Hospital | Physician in charge (Oct 14, 1609) | Daily patient care forced careful observation and disciplined notes |

| 1615–1616 | College of Physicians | Appointed Lumleian Lecturer (Aug 4, 1615); lectures began April 1616 | Repeated public dissections sharpened his methods like a weekly workout |

| 1618 | Royal court | Physician Extraordinary to King James I (Feb 3, 1618) | Court access expanded chances to observe animals, supporting hands-on inquiry |

The Medical Landscape Before Harvey

Before William Harvey came along, doctors in Europe thought they knew it all. They followed Galen’s teachings for over a thousand years. This meant they saw the body’s story as a one-way flow, not a loop.

Harvey was a game-changer. He wasn’t just debating with a few. He was challenging the most accepted ideas in medicine.

Common Blood Theories

Galen’s model saw blood as part of the four humors. It was linked to balance, mood, and health. Blood was made from food, mainly by the liver, and then moved through veins.

Arteries were seen differently. They carried a life force, linked to air from the lungs. The heart was thought to “cook” blood, not pump it.

Galen said a small amount of blood could pass from the right heart to the left. This idea helped the model seem complete, even if no one could see those pores.

Limitations of Prevailing Ideas

Why didn’t someone prove these ideas wrong sooner? The problem was the missing link was invisible. Capillaries are tiny, and without a microscope, you can’t see blood move from arteries to veins.

The old picture of the body stayed because it couldn’t be tested like we do today. Marcello Malpighi described capillaries in 1660, long after Harvey’s work started debates. Until then, the circulation of blood was hard to prove.

There were also assumptions that slowed change. Many doctors thought organs “attracted” blood when needed. This was different from a closed circuit driven by pressure and motion.

| What many physicians believed | How it shaped the cardiovascular system | What made it hard to challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Blood is continuously produced in the liver from digested food | Flow is mostly outward for nourishment, not a returning loop | No clear way to measure total output versus total supply in a living body |

| Veins carry dark, nourishing blood to be “used up” by tissues | The body behaves like a consumer of blood, not a recycler | Visible veins supported the idea of delivery without return |

| Arteries carry blood mixed with air or pneuma from the lungs | Arterial blood feels like a different substance with a different purpose | Breathing and pulse seemed linked, which fit the story |

| Small transfer happens through pores in the heart’s septum | A minimal “bridge” explains how both sides relate | The pores couldn’t be confirmed, but also couldn’t be ruled out easily |

| The heart functions mainly as a heat-maker, not a pump | Motion and pressure are downplayed in favor of warmth and vitality | No tools to track pressure, volume, and flow in real time |

Need for New Discoveries

Harvey didn’t come out of nowhere. Earlier thinkers had started questioning the old system. Realdo Colombo and Michael Servetus had already challenged some ideas. Jacques Dubois taught anatomy with respect for tradition, but the era was already tense.

What made the shift hard is that small changes didn’t change the whole picture. It took Harvey to track blood through the whole body to make people rethink their views.

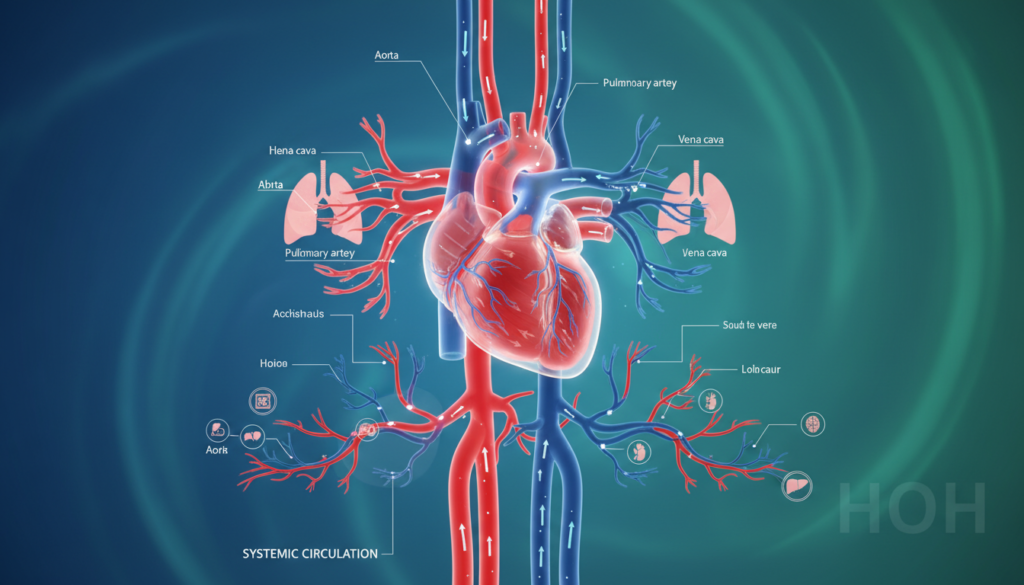

Understanding Blood Circulation

If you’ve ever watched your pulse jump after a sprint, you’ve seen a clue that fascinated William Harvey. He wasn’t chasing trivia. He was trying to explain the circulation of blood in a way that matched what the eye could actually see.

Once you start thinking like that, the cardiovascular system stops feeling mysterious. It becomes a moving loop with rules—pressure, valves, timing, and direction.

The Heart as a Pump

Harvey looked at living hearts and focused on the moment of squeeze. To him, that tightening wasn’t a quiet pause. It was the main event—the push that sends blood outward.

And here’s the wild part: he saw that a heart removed from an animal could keep beating for a while. That simple sight nudged you toward a practical idea. The heart acts like a working pump, not a gentle organ that “draws” blood in by magic.

Arteries and Veins: A New Perspective

Then he followed the plumbing. Arteries weren’t mysterious heat pipes; they were delivery routes. Veins weren’t lazy drains; they were return lanes built with valves that only allow one-way flow back toward the heart.

He also paid attention to the heart’s own valves and how they gate movement in a single direction. When both ventricles contract together, the old story about blood slipping from one side to the other starts to fall apart. He examined the wall between them and didn’t find the handy little openings people expected.

Step by step, William Harvey began to picture the circulation of blood “as it were, in a circle.” It’s a simple phrase, but it flips the map of the cardiovascular system from a dead-end road into a continuous trip.

The Role of the Liver

Before Harvey, the liver had a starring role. Many physicians treated it as the main source of venous blood, almost like a factory that made new supply nonstop.

But once you take the heart’s output seriously, that factory idea gets shaky. Harvey’s number sense made the old claim feel off. There’s just too much movement, too much volume, too much speed for the liver to be “making it all” from scratch every day while the circulation of blood keeps surging on.

So the liver doesn’t disappear from the story—but its job changes. In William Harvey’s new view, the cardiovascular system is driven by flow and return, not endless fresh production at the starting line.

Harvey’s Groundbreaking Experimentation

Ever wish medical research was more hands-on? William Harvey made it happen. He didn’t just follow what everyone thought. He looked for things he could see, measure, and test.

As an English physician, he treated the heart like a machine. This view changed everything.

Observational Techniques

William Harvey started by watching closely. He wanted to see the heart in action, not just as a static organ. But, it moved so fast, it was hard to tell systole from diastole at first.

So, he changed his approach. He used cold-blooded animals with slower hearts. This gave him a clearer view, like watching a slow-motion video.

Animal Dissection Studies

Harvey didn’t focus on just one animal. He studied different species to find common patterns. As an English physician, he focused on how things moved and functioned.

- Eel and other fish, where slower motion helped him follow the sequence

- Snail and “invisible shrimp,” chosen for what their bodies made easier to see

- Chick before hatching, where early development offered clues

- Pigeon and other birds, where the rhythm and structure gave sharp contrasts

Innovative Use of Experimentation

Harvey didn’t just watch. He also experimented by tying off vessels and dividing arteries. This showed that blood flow has a direction. His hands-on trials made his research feel more like proof.

He used simple math too. By estimating the left ventricle’s volume and multiplying it over time, he questioned how the body could keep making and using so much blood without a loop.

But there’s a twist. He couldn’t directly see capillaries. With only a tiny lens, he had to guess the small connections between arteries and veins. This built a bridge from what he could see to what he predicted, even without a clear view of the final link.

| Move | What you’d notice | Why it mattered for medical research | Real examples from William Harvey’s work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watch the heart while it’s active | Fast motion makes phases hard to separate at first | Shifts attention from theory to timing and mechanics | He tracked beating hearts instead of relying on static anatomy |

| Slow the action by choosing the right animal | Clearer, slower beats reveal sequence step by step | Makes observation more reliable and less guesswork | Eel and other fish; cold-blooded animals used for slower rhythms |

| Use “stopping” hearts to study the sequence | Motion changes gradually as the heart weakens | Lets you follow cause-and-effect in real time | Dying mammals observed as the beat slowed |

| Test one-way flow with valves and pressure | Blood moves toward the heart when valves allow it | Turns an idea into a repeatable demonstration | Pressed on veins on either side of valves; ligated an arm to show venous valve action |

| Measure volume and estimate output | Totals add up quickly over minutes and hours | Numbers challenge older “made and consumed” claims | Left ventricle volume estimates and output over time |

| Infer tiny connections he couldn’t see | Arteries and veins must connect somehow | Builds a model from evidence, even with limited tools | Predicted capillary links without being able to observe them directly |

The Publication of “Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis”

Imagine the excitement when William Harvey published his book in 1628. He chose Frankfurt for the book fair, knowing it would spread quickly across Europe. This was key because Harvey’s discovery needed to reach many, not just a few.

Importance of the Treatise

Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus was short but packed with detail. It explained how the heart works, why arteries pulse, and how blood moves. It was all about the science, not asking you to believe.

Harvey used math to show the heart’s role. He figured the heart could hold about 1.5 fluid ounces. With each beat, only a small amount leaves. This made the old idea of the liver creating blood seem wrong.

| What Harvey counted | His conservative inputs | What it suggested |

|---|---|---|

| Heart capacity | 1.5 imperial fluid ounces (about 43 ml) | The heart had enough volume to matter in big totals over time |

| Amount pushed per beat | About 1/8 of that volume (about 4.7 ml) | Small pulses add up quickly when the beat is steady |

| Beats used for the estimate | 1,000 beats per half hour | More than 10 pounds of blood “moved” in 30 minutes by his count |

| Daily implication | Extrapolated to hundreds of pounds in a day | The body couldn’t be making and destroying blood at that rate |

| Alternate summary calculation | About 1,000 fluid ounces per hour (nearly 8 gallons / 29.5 liters) | Reinforced the same point: it has to be recirculating |

Reception by Peers

Not everyone was happy with Harvey’s ideas. Some doctors disagreed, and Harvey’s practice suffered. The debate was intense, as his theory challenged old beliefs.

The book was in Latin, aimed at scholars. It took about 20 years for an English version to come out. So, Harvey’s ideas spread slowly, through debate and rumors.

Impact on Future Research

Despite the initial pushback, Harvey’s book encouraged more research. It promoted testing and counting, treating the body as something measurable. This approach was perfect for curious scientists.

Later, Marcello Malpighi found capillaries in 1660/1661. This added more detail to Harvey’s theory. For readers, it’s exciting to see how the circulation of blood was mapped out further.

Overcoming Skepticism

Imagine a room full of people who think they know everything about blood. Then, William Harvey walks in and says, “Actually, it moves in a circuit.” This was a bold move for an English physician in the 1600s. It was a challenge to the old ways of thinking.

This part of the story feels like a live debate. You can almost hear the objections and raised eyebrows. Medical research had to show results to convince people.

Opposition from Contemporary Physicians

Many doctors stuck with Galen’s model because it was familiar. Jean Riolan suggested a middle path, accepting some circulation but slowing it down. This way, critics could hold onto old ideas while acknowledging new ones.

Support didn’t always mean total agreement. René Descartes supported circulation but questioned the heart’s role. The debate drew in many, making anatomy a public topic.

Presentation of Evidence

William Harvey didn’t rely on status or speeches. He used hands-on research to prove his points. He showed how valves work and what blood does.

- Ligature tests on the arm showed vein valves work like one-way gates.

- Heart valve observations confirmed flow moves forward, not back and forth.

- Simple math challenged the idea of the liver making blood, showing it wouldn’t work.

Gaining Acceptance

There was a cost. After De Motu Cordis was published, William Harvey faced criticism. His practice suffered, but he kept working.

Over time, more people tested and discussed his ideas. Slowly, the medical community began to accept circulation. Within about 40 years, it became the standard teaching.

| Who challenged or shaped the debate | Core stance on circulation | What they emphasized in the argument |

|---|---|---|

| Jean Riolan | Partial acceptance, smaller circuit | Slower pace of movement and a reduced pathway to fit older theory |

| René Descartes | Supportive, with a different mechanism | A more machine-like body model and a disputed explanation of heart action |

| Robert Fludd | Engaged critic in the wider dispute | Big-picture natural philosophy mixed into how the body should be interpreted |

| Kenelm Digby | Participant in the controversy | Interpretation battles about cause-and-effect in living systems |

| Thomas Hobbes | Participant and commentator | Hard-edged debate style and pressure-testing claims for clarity and consistency |

The Lasting Impact of Harvey’s Discovery

It’s amazing how one doctor’s curiosity changed how we see our bodies. Harvey’s work made us see the heart and blood as a working system. This idea replaced old views that blood was used up.

This change led to new ways of thinking in medicine. Bloodletting, once common, lost its appeal. Doctors began to focus on what the heart and blood vessels do every minute.

Influence on Modern Medicine

Today, we see Harvey’s impact in many ways. Medicine now focuses on measuring things like pulse and blood pressure. This shift helped doctors understand the body better.

Harvey’s work also helped doctors find problems in the heart and blood vessels. They could look for blockages and weak spots. This new understanding changed how doctors treated patients.

| What changed | Before wide acceptance | After Harvey’s discovery spread |

|---|---|---|

| Core model of the body | Blood viewed as slowly consumed and replaced | circulation of blood framed as a repeating circuit |

| Role of the heart | More like a warming organ than a driver | Seen as a pump powering the cardiovascular system |

| Common therapy logic | Bloodletting tied to balancing excess fluid | Bloodletting faced tougher questions under a recirculating model |

| How claims were judged | Authority and tradition carried huge weight | Dissection, experiment, and rough measurement gained status |

Connection to Other Scientific Breakthroughs

Harvey’s work was part of a big scientific time. Galileo and Newton were also making waves. His discovery is seen as a key moment in medicine.

Yet, Harvey’s approach was different. He explained things in a way that wasn’t always clear. But his ideas were bold and open to testing.

Marcello Malpighi later proved Harvey right. He used a microscope to find capillaries. This confirmed the circulation of blood as a real part of our bodies.

Harvey in Historical Context

To understand William Harvey, we must step into his world. He wasn’t just adding a fact to medicine. He was challenging old ways and ideas.

Today, Harvey’s boldness is clear. He saw the body as something to watch, test, and measure. This view is key to modern medical research.

Comparison with Other Great Scientists

Harvey, Galileo, and Newton share a common spirit. Galileo focused on observation. Newton tied many facts together into a system.

Harvey, as a 17th-century scientist, focused on blood flow. He used demonstrations and numbers to prove his points.

| Figure | What they focused on | What made it feel new | Lasting ripple |

|---|---|---|---|

| William Harvey | Circulation, valves, and the heart in action | Turned anatomy into motion and used quantity to tighten the argument | Helped set the tone for hands-on medical research and testable claims in physiology |

| Galileo Galilei | Motion, measurement, and observation | Made careful watching and math feel like the main tools | Changed what “proof” could look like in science |

| Isaac Newton | Forces and unified physical laws | Built a big framework that connected many separate observations | Set a model for system-building theories across science |

The Evolution of Medical Knowledge

Medicine didn’t start from scratch. The Renaissance brought big leaps in detail, thanks to Andreas Vesalius and De humani corporis fabrica (1543). But the body’s movement was unclear.

Harvey’s work changed this. He watched hearts, checked valves, and used math to understand blood flow. This was a big shift in medical research.

Before Harvey, anatomy was like a map without traffic. His work brought the body’s function into focus. He showed how living bodies work.

There were important steps before Harvey. Realdo Colombo, Michael Servetus, and Jacques Dubois each made contributions. After Harvey, Jean Riolan and René Descartes offered different views.

But some of Harvey’s papers were lost in the Great Fire of London (1666). Historians rely on De Motu Cordis and the culture of 17th-century scientists to understand his breakthrough.

Conclusion: The Legacy of William Harvey

William Harvey didn’t just have a clever idea. He proved it. He showed the heart pumps blood in a loop through the body.

He used math and logic to show this. The numbers told him too much blood was moving. This meant blood must keep going in a circle.

Contributions to Science and Medicine

Harvey’s work was more than one big idea. He was born in 1578 and got his M.D. in 1602. He worked at the Royal College of Physicians and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

He also worked for kings James I and Charles I. His last big work was De Generatione Animalium in 1651. It was about how animals grow.

Continuing Relevance Today

Today, when we talk about the heart, we’re echoing William Harvey. He died in 1657 in London, aged 79. He was buried in Essex, in the Harvey Chapel.

In 1883, his remains were moved to the Royal College of Physicians. He left them coffee worth £56. He wanted them to meet and remember his work with coffee.

FAQ

Who was William Harvey, and why do people talk about him?

When and where did Harvey figure out blood circulation?

What did “everyone know” about blood before Harvey?

Why was Galen’s model so hard to disprove in the 1600s?

Did anyone have circulation-like ideas before Harvey?

What’s the simplest way to explain Harvey’s discovery?

How did Harvey show the heart is a pump?

What did Harvey learn from venous valves?

What role did Hieronymus Fabricius play in Harvey’s thinking?

How did Harvey use math to back up circulation?

What were Harvey’s famous pumping estimates in *De Motu Cordis*?

If Harvey couldn’t see capillaries, how did he explain the connection between arteries and veins?

What did Harvey say in *De Motu Cordis* that hints at his “aha” moment?

Where was *De Motu Cordis* published, and why there?

How did other physicians react to Harvey at first?

Who were some of Harvey’s best-known critics and debate partners?

How did Harvey gather evidence—what did his experiments actually look like?

What kinds of animals did Harvey study?

How did Harvey’s royal appointments support his research?

What was Harvey’s career path before the circulation breakthrough?

What was Harvey’s role at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital?

What was the Lumleian Lectures, and why did they matter to Harvey?

Who did Harvey marry, and did he have children?

How did Harvey’s discovery change medical practice, specially bloodletting?

How long did it take for Harvey’s circulation model to become mainstream?

What later discovery confirmed the missing link in Harvey’s circuit?

How does Harvey compare to Galileo and Isaac Newton?

Did Harvey publish anything important after *De Motu Cordis*?

What do we know—and not know—about how Harvey reached his breakthrough?

When did William Harvey die, and where was he buried?

What’s the story behind Harvey’s coffee bequest?

Get More Medical History

Join our newsletter for fascinating stories from medical history delivered to your inbox weekly.

The History of Healing

The History of Healing